'I Get to Have a Life': Pilots Speak Out on Contract Fights

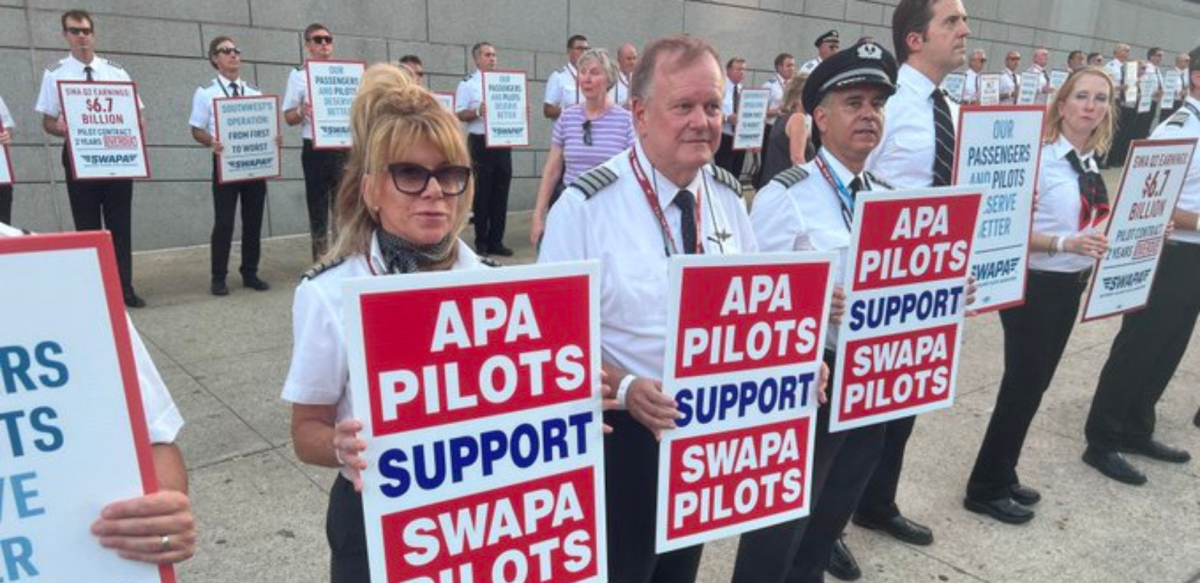

Job cuts during the pandemic have resulted in more work for fewer pilots, more fatigue, and less time at home. Photos: AFA, APA, ALPA

Airline labor is at a breaking point. The country’s four largest airlines are facing pilot labor conflicts, all centering on a mismanaged pandemic recovery.

The pilots, split among three unions, share grievances over grueling schedules. They say overwork has depleted their home lives while inflation eats into their paychecks.

Delta pilots have voted by 99 percent to authorize a strike, with 96 percent turnout. United pilots voted by 94 percent to reject a tentative agreement, and the American pilots union leadership voted not to even send their deal out for a vote. Southwest pilots filed for mediation in September, signaling that contract negotiations are not going smoothly either.

Any potential strikes are still a long way off. Airline unions are covered under the Railway Labor Act, and negotiations are subject to extensive federal oversight before any legal strike or lockout can take place.

Like the rail negotiations, the pilots’ negotiations have stretched on for years without raises. But for pilots and rail workers alike, the primary issue isn’t money—it’s time.

NOT MONEY, BUT TIME

The airline industry has gone through incredible turbulence over the past three years. When the pandemic hit, demand collapsed—by May 2020 the monthly number of U.S. flights had plunged by 75 percent.

But air traffic rebounded just as fast, shooting up 80 percent from February to July of last year.

Over the course of the pandemic, the federal government spent more than $50 billion on stabilizing the industry. That money was meant to maintain capacity for when the travel market bounced back.

Instead, airlines did the opposite—they offered buyouts, encouraging thousands of pilots to take early retirement deals. Now that shortsighted decision has left them scrambling to keep up with demand.

THE PRESSURE OF FATIGUE

The result is more work for fewer pilots, more fatigue, and less time at home.

“We had on some days a tenfold increase on pilot fatigue calls,” said American Airlines pilot Dennis Tajer. “This is not a canary in a coal mine; this is a lion roaring in the cage.”

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Fatigue calls are based on a pilot’s own judgment. Federal Aviation Administration regulations govern how long a pilot can be scheduled to work in a day, depending on such factors as start time and number of co-pilots. But pilots say what’s legal, under FAA rules and company policies, is not necessarily what’s safe or smart.

“I have to make that call,” Tajer said. “Hey, you’re legal, you can have a 13- or 14-hour day, but are you good to land in LaGuardia at midnight in a driving rainstorm? The more pressure that’s put on you, it’s pressure on the margin of safety.”

Tours of duty—known as “work blocks”—are also getting longer. Where pilots used to be assigned to leave home for one to two days at a time , now work blocks tend to be four or five days long.

This ups the stakes of calling in sick. If you call out at the beginning of a work block, you’re on the hook for four to five days of sick time. Sometimes that’s more than half a pilot’s annual allowance.

UNPREDICTABLE SCHEDULES

In response, the unions are calling for more transparency and predictability in scheduling.

Typically a pilot who is “on reserve” gets about 12 hours’ notice that they’re on the short list to get called up. That gives them time to commute into their base airport (often via commuter plane, as many pilots don’t live nearby), where they wait in a hotel room for a few hours to get the call about when their tour will begin. If someone higher in the queue calls in sick or picks up a different shift, they could get called in sooner; if there are delays, they could be held back longer.

In pre-pandemic times, this “reserve” system applied mainly to the lower-seniority pilots who didn’t yet have a fixed schedule—about 15-20 percent of the workforce, United pilots told me.

But during the pandemic, the percentage of pilots on reserve neared 50 percent. Even veterans got a taste of how broken and disruptive the reserve scheduling system has become.

The workforce reductions followed by rapid new hirings have also changed how the unions approach negotiations.

“We have about 6,000 pilots who weren’t here last time we went through negotiations,” said Shane Corbett, a six-year Delta pilot. “We’ve had a generational shift; the folks that are being hired now have a different idea and perspective. They expect the company will give us better benefits when it comes to a work-life balance.”

Tajer agrees. “We have a younger generation,” he said. “They’re like, ‘Look, I get to have a life. I’m not going to be my dad.’”