Toledoans Rally behind Hospital Strikers

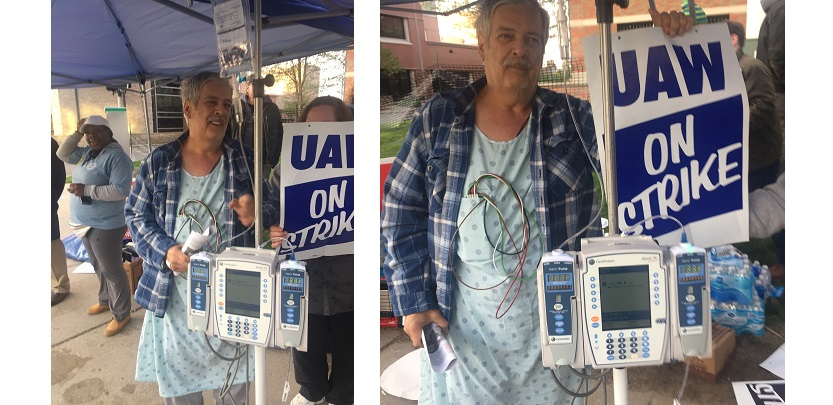

Bill Hornyak, a former Teamster now on disability, came out of his hospital bed to join the workers on strike at Mercy Hospital in Toledo. Hornyak said he’d had a previous heart attack a month and a half ago, and “these people took real good care of me.” When his batteries began to run low, Hornyak went back inside. Photo: Jane Slaughter.

Being on strike is “kinda scary,” said one picketing nurse in Toledo, Ohio—but “kinda empowering,” broke in another. “We’re doing this for nurses across the board.”

After 58 bargaining sessions totaling 450 hours since last summer, nearly 1,900 hospital workers at Mercy Health St. Vincent walked off the job Monday, marching from union headquarters to line the street in front of the hospital.

If honks are the metric, the strikers seemed to have enthusiastic support from Toledoans on a cold and windy Wednesday night. “Toledo is a union town,” several strikers said. Machinists from Libbey Glass on the line said they’d struck for 13 days in 2016 and were paying back the solidarity they’d gotten then.

Bill Hornyak, a former Teamster now on disability, left his hospital bed, dressed in a thin gown and wheeling his IV pole, to show his support. “I had a heart attack a month and a half ago and these guys took real good care of me,” he said.

The strikers include nurses, nurse aides, respiratory therapists, housekeepers, dietary workers, and many others. Their issues are similar to those of other health care workers who’ve struck in recent years.

First is inadequate staffing. Nine hundred nurses now do the work of the 1,200 who worked at St. Vincent years ago. “We want safe patient ratios,” said eight-year RN Jennifer Horner. “They [management] will change a patient’s acuity so they can give a nurse more patients.” (“Acuity” is a measure of the intensity of nursing care required.)

Luis Soto, who works in sterile processing, said his co-workers are “constantly behind” and that St. Vincent “has never had full staffing since I started.”

Chris Upperco, an oncology/med-surg nurse, said that three years ago, she had time to “find out what is going on in our patients’ lives that could contribute to why they’re here. We could do education with people to help them understand how to take care of themselves in the future. But if we don’t have time to talk....”

Upperco said she’d recently seen two nurses and one tech having to care for 22 patients.

The understaffing leads to “floating,” where nurses are required to move to areas they’re not specialized in, based on patient census: pediatric nurses to the heart unit or cardiac nurses to obstetrics.

ON CALL

Management’s solution to chronic understaffing is to require workers to be on call—and 90 percent of the time, they are in fact called, Upperco said. The rules vary by department, but RN Kim Evans said a surgery nurse working five eight-hour days during the week could also be on call for 24 hours on the weekend, or a nurse with a 36-hour work week could be forced onto an additional 12-hour on-call shift.

Housekeeper Liz Taylor talked of often being “frozen over”—required to work six more hours after her eight-hour shift. “If you start at 3 p.m. you’re working till 5:30 a.m.,” she said. “And you get ‘pointed’ if you don’t.”

Taylor wanted to know where, with the perpetual understaffing, all the scabs were coming from.

Tiffany Evans, a patient care technician, said management is always trying to get workers to come in early. “They are getting over on us,” Evans said. “They think, ‘They need this job, so we’re going to do what we want to do.’”

OUTRAGEOUS DEDUCTIBLES

Mayor Weighs In

Mayor Wade Kapszukiewicz pointed to the “nonstop cacophony of sound” in front of the hospital, “of horns honking of support, of endorsement from average citizens... just the average joes and janes of Toledo.”

He urged the sides to return to the table, noting that “Mercy needs to actually be willing to make constructive suggestions and make progress on some of the areas where there’s an impasse. It’s not enough to meet, where the meeting would simply lay the groundwork for future considerations of eventual savings that could perhaps one day, after task forces are formed, move the needle....

“Toledo is perhaps the latest battlefield in a war over health care costs, corporate profits, the welfare of workers. It’s been going on for hundreds of years.”

Another strike issue is insurance. Strike captain and RN Rick Hannum said employees are required to use Mercy facilities, but at high cost. Current deductibles are $750 for a single worker and $1,500 for a family. Now management wants $2,000 and $4,000, with no cap on workers’ out-of-pocket health care costs.

At one point negotiators proposed using the maximums allowed under the Affordable Care Act for a marketplace plan: $7,900 for an individual and $15,800 for a family. Soto said, “They want us to just leave the cost up to them in the second and third years.”

Members of UAW Locals 12 (techs and service workers) and 2213 (RNs) rejected an earlier management offer by 80 percent and 90 percent, respectively, and the strike vote was 90 percent to walk.

The union has filed unfair labor practice charges, saying management told workers that if they struck, they would have to use their accrued time off.

On Day 3 of the strike, the list of organizations and small businesses supporting the strikers reached 50, said United Auto Workers (UAW) Local 12 spokeswoman Sandy Theis. “I’m not aware of anyone who’s stepped up to support the hospital.”

On Mother’s Day the majority-women workforce will be bringing their kids to the picket line.

CORRECTION: This article originally stated that current deductibles were $2,000 for an individual and $4,000 for a family. In fact that's what management is trying to raise them to. The current deductibles are $750 and $1,500.