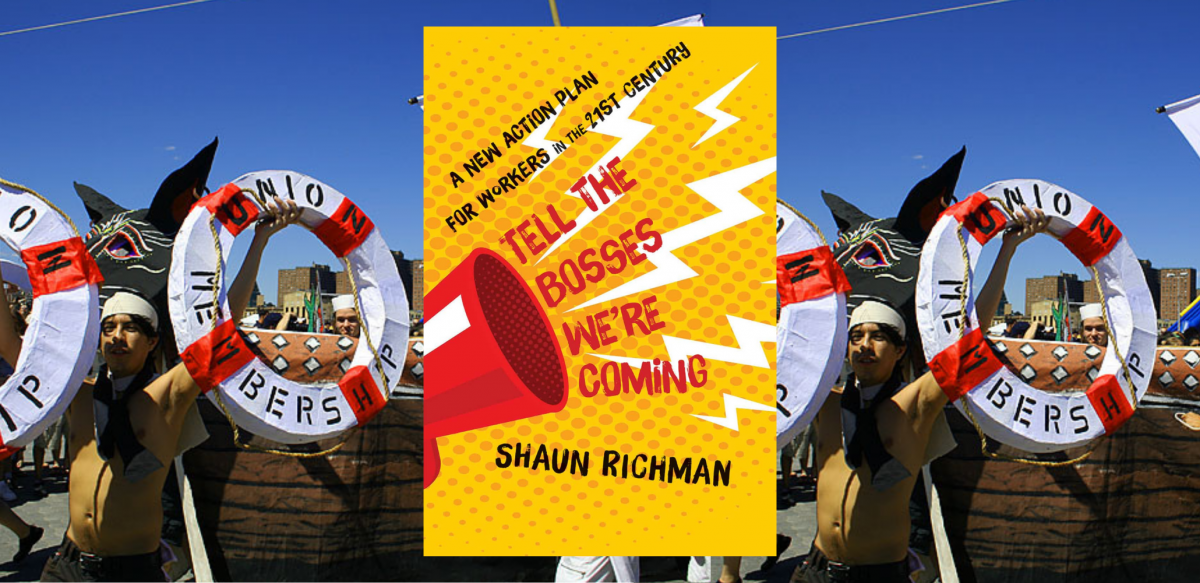

Review: Tell the Bosses We’re Coming

Tell the Bosses We’re Coming: A New Action Plan for Workers in the 21st Century, by Shaun Richman (Monthly Review Press, May 2020, 256 pages). Photo: M. Bitter, from an IWW float at the Coney Island Mermaid Parade in 2007 (CC BY-NC 2.0)

American unions are stuck in a trap, and it’s partly of our own making. How did we get here, and how do we spring the trap’s jaws? In Tell the Bosses We’re Coming: A New Action Plan for Workers in the 21st Century, Shaun Richman draws on his experience as a union organizer, plus a great deal of labor history, to suggest answers to these questions.

Like any good organizer, he’s not afraid to ask hard questions: Is what we’re doing working? If not, why do we keep doing it? If we could wipe the slate clean, what kind of labor movement should we build?

AN EARLY TRADE-OFF

Let’s start with collective bargaining. In Richman’s telling, much of how we behave at the bargaining table today can be traced back to the Treaty of Detroit, the landmark 1950 contract between the Auto Workers (UAW) and the Big Three automakers.

Five years earlier, the UAW had struck, unsuccessfully, for a 30 percent raise and no increase in the price of automobiles. In 1950, in exchange for annual raises and health, vacation, and pension benefits, UAW members gave the companies a management rights clause and five years of labor peace with a no-strike clause. Together, these clauses strongly curtailed auto workers’ voice in shop floor issues that arise mid-contract.

Today, management rights and no-strike clauses are treated as so routine that unions sometimes agree to them prior to settling the rest of the contract.

As Richman puts it, “We have capitulated to the position that the boss gets to run his business, and we just get to ask for more money. This is, literally, not what workers want.” A living wage and decent benefits are important, but people also want a meaningful say over their work lives.

So why don’t we do things differently? In short, Richman argues, the legal framework our unions operate in makes it hard to escape, particularly as a result of “exclusive representation”: the idea that a single union represents all workers in a given bargaining unit.

Richman points out that exclusive representation wasn’t baked into the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) when it was passed in 1935, but instead is tied to the rise of the Congress of Industrial Organizations, which split from the American Federation of Labor in 1935.

The CIO believed it was better to organize workers into unions by industry (for instance, railroad workers) rather than by craft or job title (for instance, train engineer). It pursued a strategy of representing all job titles in a workplace, and all workers in those titles, to build greater power within industries through density and to block the AFL from gaining footholds in the shops the CIO was organizing. The model of exclusive representation developed out of this strategy.

Because of exclusive representation, all bargaining-unit employees are bound by the no-strike and management rights clauses. So what happens when workers band together mid-contract to demand more, or to protest negative changes in their working conditions? Union leaders are forced to oppose their own members’ efforts or face legal injunctions and steep financial consequences—since work stoppages, labor’s greatest weapon, are mostly unprotected by the NLRA.

Where does this leave us? With a labor movement that’s on the defensive, trying to organize shop by shop and maintain “the union advantage” over non-union workers in order to attract new members, even as union benefits are being dismantled.

THE LABOR MOVEMENT, REIMAGINED

Tell the Bosses We’re Coming is full of proposals to transform and reinvigorate the labor movement. Richman argues that only by rekindling what he calls a “culture of solidarity” can the labor movement create the conditions necessary to organize. For starters, he asks organized labor to fight on behalf of all workers, not just those currently in unions.

What does that look like? The labor movement should fight for national legislation to win Medicare for All and end at-will employment so that all workers have just-cause protections. These wins would provide all workers with more security on the job and neutralize the fear of firing that prevents them from organizing.

Richman has other big policy ideas, like national government “industrial labor boards”—one for each industry—that would have the power to raise wages and “settle big ticket work rules and benefits across entire industries.”

He talks refreshingly in terms of “rights,” such as the right to one’s job and the right to strike. In doing so, he advances an argument that predates the passage of the NLRA: that workers’ rights should be based on the First, Thirteenth, and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution rather than the Commerce Clause—and that we should advance a strategic flood of legal challenges necessary to cement them as such.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

While Richman argues for fostering a culture of solidarity in the labor movement, he also proposes a heretical idea: with mandatory union membership under attack from the right, why not just ditch exclusive representation entirely? This would solve labor’s “free-rider” problem under Janus and, Richman optimistically suggests, create an opening for new groups of workers to band together, unbound by existing contracts’ management rights or no-strike clauses, to demand and win better agreements for themselves. These victories, Richman argues, could then be shared with the members of all unions in a given shop through a bold application of the NLRA’s Section 8(a)3 protections against discrimination on the basis of union membership.

Viewpoints: Exclusive Representation

One of Shaun Richman’s arguments in this book is that unions would be better off if we abolished the framework of exclusive representation. Labor Notes in 2018 published a debate featuring a variety of perspectives on whether unions should seek to change the law, as well as how they should deal with the free-rider problem under the current law:

Introduction: How Should Unions Deal with Free Riders?

Chris Brooks: Don’t Fall for the Members-Only Unionism Trap

Steve Downs: Don’t Rule Out Giving Up Exclusive Representation

Jonathan Kissam: Unions Are Class Organizations, and Should Act Like It

Marian Swerdlow: To Thrive after Janus, Deeper Changes Are Needed

Les Caulford: An Injury to the Contract Is an Injury to All

Bruce Nissen: How One Union’s Image Got an Upgrade

Joe Burns: Making the Union a Personal Choice Gives Ground to the Boss

Taken together, Richman’s proposals and his Labor’s Bill of Rights can be contradictory—he proposes an “all-in” system of labor relations but suggests ditching exclusive representation—and at times meandering, but they sketch out a hopeful vision of what could be possible if we rebuilt our system from the ground up.

WE ARE THE ACTION PLAN

Though it has “plan” in its title, where Richman’s book feels most incomplete is its lack of a roadmap for how we actually accomplish any of these proposals. After all, implementing even a fraction of them will take real power. Our current political moment makes that hard to imagine, and Richman acknowledges that. What are we to do?

At the end of the day, it’s up to us. To his credit, Richman does highlight a number of changes that we have the power to make. Union members shouldn’t get stuck in what Richman calls “the routine of collective bargaining.” Learn the date of your next contract expiration and push to align it strategically with others in your shop or industry. Get management rights clauses out of your contract; given the NLRB’s recent MV Transportation ruling, this is more important than ever.

As far as organizing strategies, Richman’s points—target strategic industries and use comprehensive campaign tactics while developing rank-and-file leadership—will sound familiar to Labor Notes readers.

He also emphasizes that we should push our unions to fight for labor law reform. Congressional Democrats’ PRO Act would re-legalize secondary strikes and boycotts and establish the first-ever penalties for employers who violate labor law. This is only a start. We should make bold new constitutional arguments to secure a real right to strike and to return to work. We must repeal Taft-Hartley, and we should fight for an NLRB that isn’t starved of resources.

Even under (and at times, despite) our current system of labor relations, the labor movement has many bright spots. Last month Mission Hospital nurses in Asheville, North Carolina, won their union in the largest union victory in the South in a decade. Last year non-union coal miners staged a railroad blockade to win unpaid wages. Over the past few years, teachers in Chicago, West Virginia, and Los Angeles have struck and won victories for the common good.

Tell the Bosses We’re Coming challenges us to think of how we can extend the labor movement’s gains. Richman’s proposals would transform the way our unions operate, and they’re not without downsides—but, with union density at historic lows, his ideas merit consideration.

Tyler Kissinger is an organizer with the National Union of Healthcare Workers. He can be reached at @tylerbkissinger on Twitter.