The Amazon Imperative: Unions Must Join Forces

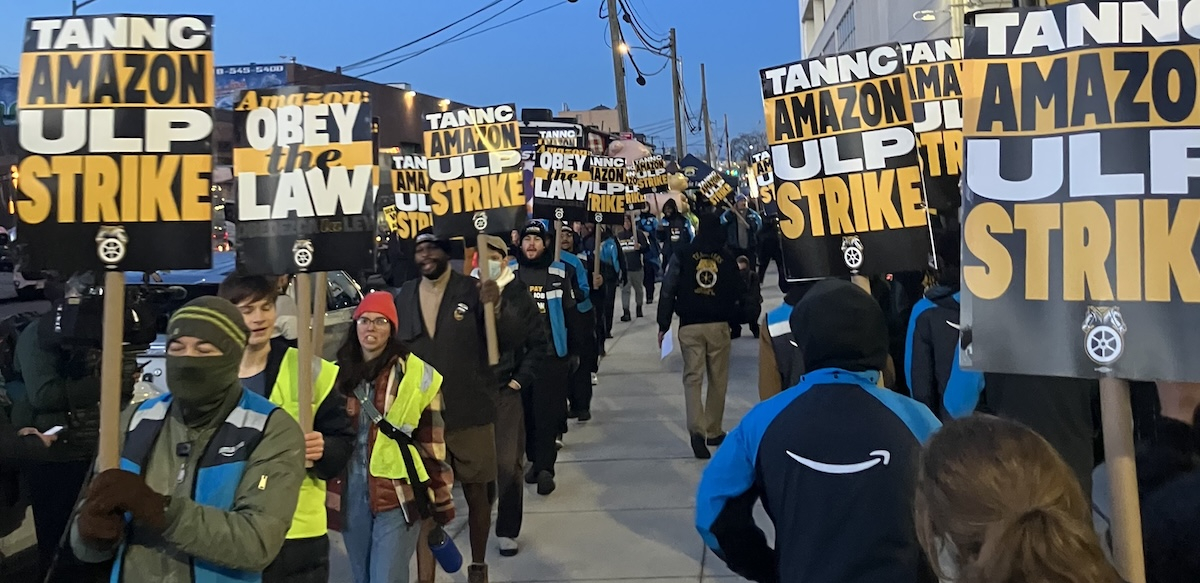

Workers picket outside an Amazon delivery station in Queens, New York, in December. Photo: Max Fisher

The tentacles of the global logistics juggernaut Amazon reach into every corner of the economy, gripping the planet and workers. Amazon dominates retail e-commerce with a 40 percent market share. It is making major inroads into health care (One Medical), grocery (Whole Foods), Hollywood (Amazon Studios MGM), information technology (Amazon Web Services), and artificial intelligence.

Amazon’s operations are full of flashpoints for potential resistance. Its warehouses are rife with safety violations and record injury rates. Its web services collaborate with Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents, facilitating the Trump administration’s assault on workers and rights.

Its stranglehold includes sectors where workers have major leverage because they are key to the economy. Take international transport, where Amazon is now a Non-Vessel Operating Common Carrier, meaning it provides shipping services for customers without owning any ships. There has even been speculation that Amazon might seek to operate the Port of Pittsburg, California—upriver from Oakland—to bypass the power of the dockworkers in the Oakland Bay Area, and eventually have its own fleet of ships.

The stakes are high for U.S. labor. If we are going to remain relevant, unions must meet the challenge of building worker power at such a behemoth by making Amazon organizing a project of the entire labor movement. It will require bold initiatives and an ecumenical approach. Organizing Amazon is our do-or-die test.

As Amazon continues to spread into new markets, it is a threat to labor standards that many unions have achieved in their jurisdictions. These unions have a self-interest in supporting a broad campaign to protect their existing contract standards by improving conditions for Amazon workers.

METRO STRATEGY

For an organizing strategy to succeed, it has to locate Amazon’s vulnerabilities. We believe that these vulnerabilities exist primarily in metropolitan areas, where there are huge markets, sympathetic communities and elected officials, and where on-time (and now even same-day) Prime deliveries are susceptible to work stoppages or slowdowns.

Metro regions like New York City or greater Los Angeles are not only strategic because of the particular facilities that are “chokepoints,” but also because sympathetic elected officials there can support worker power through pro-worker legislation.

Ten states, including California, Texas, Florida, Georgia, Arizona, and New Jersey, are major Amazon employment clusters with 30,000 workers or more. Each has inbound cross docks, which are holding facilities close to ports and railyards, where products arrive via trains and ocean containers, and are sent out to inland warehouses for fulfillment and delivery. The cross-dock facilities are highly vulnerable to a work stoppage because, unlike fulfillment centers, they have little or no redundancy. Just two inbound cross docks in the Inland Empire east of Los Angeles in Ontario and San Bernardino account for the majority of container traffic from the Ports of LA and Long Beach.

Further down the supply chain in metro regions, strikes at a critical mass of delivery stations in a given area could substantially interfere with on-time product delivery to customers, though Amazon has expanded its subcontracted Flex drivers to undermine any strike. But speculation about choke points is academic until we actually get to the point of measuring the impacts of worker actions that disrupt the supply chain.

SAND IN THE GEARS

Another crucial arena is the role that particular workers play in Amazon’s logistics and information systems.

Amazon is investing heavily in automation, with Kiva robots proliferating in its large fulfillment centers. These robots are maintained and repaired by Reliability and Maintenance Engineering workers, who complete a “mechatronics and robotics apprenticeship” and hire in as subcontractors, earning more than $30 an hour. They are usually electricians or workers from other skilled trades. Could these “mechatronic” workers play a strategic role similar to cutters or upholsterers in garment and furniture factories?

Conveyor belts are crucial to the movement of goods in a modern warehouse. Skilled millwrights build and maintain these systems of product distribution and transport. If a solid core of these strategic workers were organized, could short strikes bring the system to a halt?

Another group of workers who wield significant power are employees who write programs and algorithms that enable on-time deliveries. On several occasions, glitches in computer systems have led to massive delays. Amazon Employees for Climate Justice has been organizing these strategic workers to protest company environmental policies.

AECJ leaders and organizers have also begun to concern themselves with the working conditions of tech workers and solidarity with other Amazon employees. More than 1,000 Amazon employees and nearly 4,000 supporters recently signed a warning that the rapid A.I. rollout threatens jobs and climate.

These critical analytical assessments are now part of the ongoing work of the union organizers and “salting” activists (those who take jobs to organize from the inside) seeking to build worker power at Amazon.

LABOR-COMMUNITY ALLIANCES

Workplace action at Amazon must be accompanied by strong labor-community alliances and wielding political power in Amazon’s sensitive jurisdictions, like ports and urban strongholds.

New York City Mayor Zohran Mamdani may afford labor a unique opportunity. The Teamsters are demanding hearings on a proposed Delivery Protection Act, which would require delivery companies in New York City to directly employ their workers and take responsibility for their safety.

Elsewhere, state ballot initiatives and legislation could impede Amazon’s super-exploitative delivery model, strengthening labor’s hand. The Athena Coalition has spotlighted successful efforts to pass legislation in California, New York, Minnesota, and Washington to combat Amazon’s injury rates by regulating exploitative productivity quotas.

None of these metro and state initiatives will be successful without an ecumenical approach by a coalition of unions. No one union can do it alone. While jurisdictional claims should be respected, success will require each participating union to subordinate its parochial interests to a strategy of unified action directed at Amazon.

AMAZON LABOR TABLES

A metro strategy would entail building Amazon “labor tables”—regular meetings where unions agree to coordinate their efforts—in some key metro areas, where there is interest and resources. These tables could be initiated by the most committed national unions or be built from the bottom up. Additional resources could be provided by the AFL-CIO.

Regardless of how they are built, a successful Amazon table would need some or all of these elements:

- Unions pledging significant financing. Contributions and staffing commitments will be the most difficult to work out, but participating unions should commit to a multi-year budget in support of a local metro table’s efforts.

- A credible, neutral convener such as the Central Labor Council or labor education or research center. The convener must have the respect of the unions, and the clout to facilitate consensus.

- An organizer assigned to keep the ball rolling between meetings and spearhead an ongoing effort to recruit additional unions and organizers.

- Research capacity, provided by a local labor education or academic program.

- Amazon rank-and-file organizers should be welcome participants. These meetings could become an important way to recruit and sustain salts.

Metro labor tables could help forge productive relationships with local or regional groups working on Amazon-related issues like the impact of Amazon Web Services data centers and A.I. on climate change and the environment. Periodic national calls could be used to share progress and best practices from one metro area to another. Experience in the struggle will build the trust and confidence needed to escalate actions and evaluate their effectiveness.

Local solidarity would lay the groundwork for nationally coordinated actions. As the local work gains traction, national union leaders are more likely to increase their commitment to this crucial task of our time.

JOINT CAMPAIGN

Amazon organizing isn’t starting from scratch; we just need to coalesce the various efforts into a coordinated campaign. In 2021, the Retail Wholesale and Department Store Union, an affiliate of the Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW), made history by being the first union to have a National Labor Relations Board-supervised election at Amazon. While the vote was a loss, massive media coverage made it the shot heard round the world. The company’s gross violations of labor law led to a rerun in 2022; the union lost again, but by a closer margin. Contested ballots and unfair labor practices will probably lead to yet another election.

Meanwhile, also in 2022, an independent union won a thrilling first-ever NLRB election victory at Amazon’s enormous Staten Island fulfillment center. In a speech to the AFL-CIO Executive Council, Mark Dimondstein, then president of the Postal Workers (APWU), challenged the whole labor movement to support Amazon organizing. His plea fell largely on deaf ears.

Since then, the Teamsters union has been the most high-profile contender with Amazon, and in a hopeful sign, the independent union on Staten Island affiliated with it. Along with an aggressive legal strategy, the Teamsters have supported warehouse workers and delivery drivers in dozens of mini-strikes and other concerted actions. However, despite the union’s size and strength, it is hard to believe the Teamsters have the resources to organize all 1.1 million U.S. employees at over 600 warehouses.

Fortunately, other unions are beginning to enter the fray. UFCW has organized a Whole Foods market in Philadelphia—although, like at the Staten Island warehouse, Amazon has thus far refused to negotiate with the union. The APWU has supported Amazon workers organizing in Detroit and other locations. And recently, the Service Employees (SEIU), the AFL-CIO’s largest affiliate, has committed to providing resources in support of organizing.

Ignoring the threat to labor standards and union values posed by Amazon won’t make organizing any easier next year. The union movement has the people power and resources. The Teamsters, independent unions like CAUSE, and several worker centers have built committees leading to successful workplace actions. These committees have boosted on-the-job solidarity, won concessions from management, and generated community support. However, sustaining the work means taking the organizing to a higher level with more resources and a broader commitment from the entire labor movement. Metro Labor Tables would be a good first step.

Peter Olney is retired organizing director of the Longshore Workers (ILWU) and a co-editor of Labor Power and Strategy. Rand Wilson has worked as a union organizer and labor communicator for more than 40 years. He is currently an organizer for CHIPS Communities United.

You must log in or register to post a comment.