Id like to send a donation to

Id like to send a donation to the strikers hardship fund. Where can I send it?

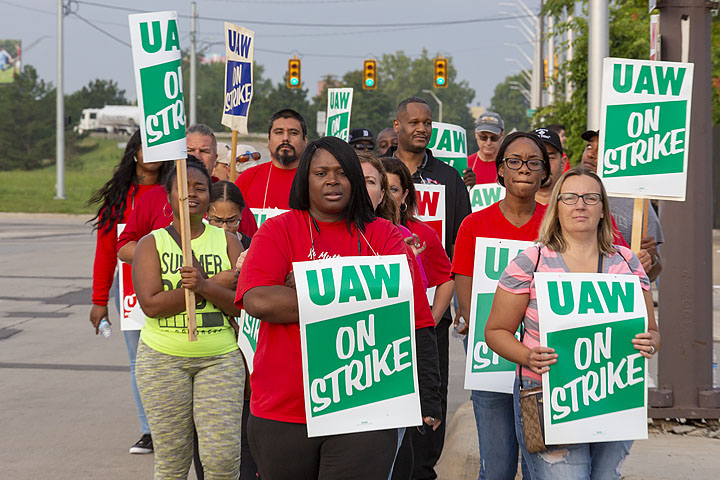

Anxious auto workers across General Motors walked out on strike Monday morning, making a stand against their two-tier system. Photo: Jim West/jimwestphoto.com

Forty-nine thousand auto workers are on strike at General Motors in the largest private sector strike since the last time union and company clashed, in 2007.

(Ready to lend a hand? Click here for a list of picket line locations.)

Production has stopped at 55 factories and parts centers. According to various analysts, the strike could cost GM $50 million to $100 million per day in profits. Before the strike, the company was expected to make $3.5 billion in this quarter alone.

Walking out was “scary and uplifting at the same time,” said Shawn Edwards, a worker at GM’s Detroit-Hamtramck assembly plant with three years’ seniority. “It’s scary because we have lives to maintain and we don’t know how long we’ll be out. We don’t want it to be too long but we do need to make a statement.

“It’s uplifting because we’re making a stand,” she said. “We’re not accepting concessions from a company posting billions of dollars of profit. And because we’re all together. There’s safety in numbers. We’re standing up for ourselves in solidarity.”

Strikers are hoping to make up ground lost since the United Auto Workers agreed to two-tier wages in 2007, followed by the Great Recession and the auto bailout, when GM got $50 billion from the taxpayers and even more concessions.

The company has since rebounded, making $35 billion in profits over the past three years. GM paid no federal income taxes last year and gifted CEO Mary Barra $22 million.

Yet union workers, whose contracts were once the lodestar of the private sector, continue to fall behind as GM fills its factories with low-paid temps, contractors, and a subsidiary called GM Subsystems—all doing work once performed by regular GM employees. As one indication of the slippage in union numbers and power, when the UAW struck GM for two days in 2007, the workforce was half again as big, at 74,000, as it is today.

Not satisfied, GM is demanding more concessions from its overworked employees, a sign that the company sees the UAW as an easy foe, especially given the highly publicized corruption scandal that has rocked its top leadership.

It’s a testament to the rank and file that despite everything—not only the scandal but also the lack of any preparation through a contract campaign—they walked out as one. Even as their leaders kept mum about bargaining goals in the lead-up to the strike, auto workers decided what they were prepared to fight for.

Picketers on the line September 16 at GM’s Detroit assembly plant all said that equality for temps and second-tier workers was their priority.

General Motors broke its contract with the UAW when it announced the closing of four factories late last year. Since the 1980s, auto contracts have included language forbidding plant closings, and yet the companies have continued to “idle” plants at will. In 2018 the term was “unallocated”—no new product was assigned.

When the closings were announced last Thanksgiving, cynical auto workers said the company was making these threats as bargaining chips. Sure enough, GM is now offering to build electric trucks at one unallocated plant and electric batteries at another, with a small fraction of the former workforce.

Today, contracted-out janitors in the plants make as little as $15 an hour, but in the past they would have been direct employees of GM and covered under the auto contract, which pays Tier One “legacy” workers about $31. Such jobs were often reserved for employees with high seniority whose bodies were worn ragged from years on the assembly line. Today most such jobs that GM considers ancillary, such as sequencing parts to feed the line, are done by contractors.

GM’s plant in Spring Hill, Tennessee, for instance, is wall-to-wall UAW, with 5,200 employees. But only 3,600 are under the GM contract. The others are considered “supplier partners” and work for independent companies on site.

At the GM Tech Center where Jessie Kelly works, outside Detroit, she said there are 1,300 workers employed by GM and 550 employed by Aramark, doing both janitorial and skilled trades work.

Michael Mucci, a carpenter at Detroit-Hamtramck, said he has literally taken his father’s job—but his father’s employer was GM and his is Aramark. “I’ve got the same bosses he had,” Mucci said.

In another concession long sought by the auto companies, Aramark does not employ carpenters per se. All the traditional trades are dissolved into either “mechanical” or “electrical.”

GM weakens standards further by relying on so-called temporary workers, or “permatemps”—workers who perform the same jobs as regular workers, for far less pay—around $15—and worse benefits.

“As a temp you have absolutely no rights,” Kelly said—she is a former temp—and they may remain temporary for years. Temps are allowed to miss only three days of work per year, unpaid, with advance approval, and can be forced to work seven-day weeks. Many stick it out for years, as Kelly did, in hopes of eventually being elevated to what GM calls “in progression” status (Tier Two).

“The last week of February when the profit-sharing checks come, we have two workers standing side by side that have done the same job all year long and one gets $11,000 and the other gets nothing,” said Michael Herron, UAW Local 1853 chairman at Spring Hill.

When temps were first allowed years ago, the Big Three automakers (Ford, GM, and Chrysler) said they would fill in for absentees. But now GM says 7 percent of its blue-collar workforce is permatemps. According to Herron, there are over 200 at Spring Hill.

“These aren’t workers just filling a 90-day hole so that another worker can go on vacation,” he said. “They have worked every week for three years non-stop. So they deserve to be compensated just like anyone else.”

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Striking auto workers are trying to climb out of the hole they are in, but leaders have done little to offer a ladder. International leaders organized no contract campaign to energize members and pressure management before the strike and did not publicize their demands. Picket signs say simply “UAW on Strike.” At the Detroit-Hamtramck assembly line, a supporter was told not to carry his handmade “Solidarity” sign; only the official signs were welcome.

Not a button was distributed in the plants. There was no survey of the membership, no rank-and-file contract action teams, no bargaining bulletins to keep members in the loop. No “practice picketing,” no turn-down of overtime, no outreach to the public, no open bargaining—none of the tactics that have become common in many unions.

As they have for decades, UAW officials played their cards close to the vest, with only management allowed a peek. Members knew what they read in the media, explained materials handler Sean Crawford at Flint Assembly.

And the strike got off to a bad start when union leaders directed GM workers to cross their fellow union members’ picket lines.

About 850 Aramark janitors represented by the UAW at five GM plants in Michigan and Ohio had been working without a contract for over a year. They struck at 11:59 pm September 14—the same time the big UAW contract expired. But GM employees were told to report to work without a contract, despite the pickets. After one more day of production for GM, their strike began 24 hours later.

“I can’t imagine a worse way to start a strike,” said Crawford, who took a personal day to keep from crossing the line. “The sit-downers would be rolling in their graves.”

Given GM’s massive profits, the UAW was well positioned to turn this strike into a national referendum on corporate greed and get the public behind workers’ demands, much as the Teamsters did during the 1997 strike at UPS that proclaimed “Part-Time America Won’t Work.” More recently, teachers have demanded “the schools students deserve.” Sadly, until the strike began the UAW made no attempt to connect auto workers’ issues to something the public could get behind.

GM wants members to pay more for health insurance and is offering a less-than-inflation raise: 2 percent in the first and third years and 2 percent lump sums the second and fourth years. Worse, it offers no movement on the odious tiered system.

A sign of the company’s hardball stance was that it stopped paying for strikers’ health insurance; the union will pick up the tab for partial coverage. In earlier decades, the auto companies continued to pay for insurance right through strikes.

Complicating the strike is the corruption scandal that has now reached the union’s top levels. The houses of President Gary Jones and former President Dennis Williams were searched by the FBI August 28.

Jones’s top lieutenant before he became president, Vance Pearson, was charged with using union funds for personal luxuries, and it’s widely believed that Jones and Williams will be next; they are cited as “UAW Official A” and “UAW Official B” in court documents.

Pearson, who remains on the UAW executive board and reportedly attended bargaining after the contract expired, was the sixth UAW official to be recently charged with or convicted of graft; another was a vice president and a third the top aide in the union’s General Motors Department.

Crawford said as the strike kicked off, “Yes, the UAW is corrupt. It’s disgusting beyond belief. But this is not about them. It’s about us. We can and will clean house. But we have a more immediate fight on our hands right now.”

Kelly too wanted to rally the troops against GM: “If somebody in the union abused their power, their future is already set out for them. Ours is not, ours is up in the air. All we can do is be there for each other because if we lose sight... GM will win because we were focusing on the wrong fight right now.”

Mitch Fox, now at Romulus Engine near Detroit, his third GM plant after numerous shutdowns and layoffs, thinks his officers’ disrepute could even be a motive for the strike: “With everything that’s going on, maybe they’ll try harder to gain our respect back; hopefully that’s the plan.”

But if past contracts are an indication, the pact Jones negotiates is likely to be weak. If the strike is meant to wear down members rather than GM, leaders may accept a deal with a big signing bonus and plenty of tiers.

In that case, GM strikers will have just one tool to use between their rock and their hard place: their right to vote no. They can do what Chrysler workers did in 2015: they organized to turn down a contract that enshrined the two-tier system.

Rank-and-file Chrysler workers, with no union support, made leaflets and T-shirts, created Facebook groups to share their tactics, and rallied outside informational meetings.

They did what no one thought possible in the UAW and voted Williams’s offer down 2-1, overcoming his defiant declaration that “ending two-tier is bullshit!” and winning a partial victory. The offer was improved, establishing an eight-year grow-in to full pay for second-tier workers, in a four-year contract (though still without pensions or an equal health care plan).

Soon after the Chrysler vote, perhaps emboldened by the “no” vote there, GM skilled trades workers rejected their pact as well, by almost 60 percent, winning some improvements. (Production workers voted yes by 58 percent.)

In 2015 what the automakers gave with one hand they took away with another, though—a less-noticed provision also increased the use of temps.

“I’m voting no on any contract proposal that doesn’t give a pathway to equality for every GM/ UAW member,” said Crawford. “This is a sacred principle. It is the very meaning of the word union. This opportunity might not come again.”

This article has been updated from an earlier version published September 16.

Id like to send a donation to the strikers hardship fund. Where can I send it?

Slaughter and Brooks say, “GM strikers have just one tool to use between their rock and their hard place: their right to vote no.”

However, rejecting a contract is not enough to get the GM strikers out between their rock and their hard place. And it isn’t the only tool they can use, either.

First, it isn’t enough. Slaughter and Brooks themselves show why. They give the example of 2015 Chrysler workers organized and rejected their TA. Slaughter and Brooks themselves say, “the offer was improved, establishing a ‘grow-in for second-tier workers to full pay, (though still without pensions or the same health care plan.)” They don’t mention how long that “grow-in” takes, either. They mention the GM skilled trades workers rejecting their TA, “winning some improvements.” It’s clear from these examples, which are similar to the results of many other contract rejections, all that is achieved merely by voting down a contract is . . . some improvements. However, GM strikers want more: a quick and complete end to tiers, no concessions, and no more plant closures. They are not going to achieve these goals simply by voting down the deal management and union heads offer them. Contract rejection is a necessary, but not sufficient condition.

Second, it is not the “just one” tool the strikers have. Voting down a contract takes organization. As workers organize to “vote no,” they can also organize discussions directed at the question: “What would it take, how could we inflict enough pain on GM, to win all of our demands?” An accurate answer to this will almost certainly involve actions that violate the spider’s web of anti-labor laws developed for the very purpose of criminalizing the actions that workers need to take to protect their interests. During the 2018 Red State teacher strike wave, people began to remember, “There are no illegal strikes, only unsuccessful ones.” A corollary to that is, “There are no illegal union tactics, only unsuccessful ones.” Once strikers have agreed on what it will take to win a victory, they can publicize and popularize it, pressure the union leaders to carry it out, or take matters into their own hands and carry it out themselves.

Meanwhile, GM must not be allowed to “starve” out the strikers. Strike pay of $250 a week stamps a quick expiration date on the strike. The UAW strike fund exceeds $750 million, and is constantly being replenished by the vast majority of UAW members who are not on strike. The current kitty could pay each of the 50,000 strikers $1,000 a week for almost four months. Organized strikers could also pressure UAW leaders to appeal to the solidarity of all its members by asking them to increase their payments into the strike fund for the strike’s duration. Finally, organized strikers could ask locals of other unions, labor groups and individuals to “adopt a striker family” to help them out financially for the strike’s duration, as was done, for example, during the P-9 strike in the mid-1980s.

Finally, out of strikers organizing to vote “no” and to develop and implement a strategy to win, could come the kernel of a continuing rank and file organization that could challenge and provide an alternative leadership to the corrupt and incompetent incumbent UAW leadership.

A “no vote” would be a major step, but it would be just the beginning. And it is not the “one tool” the GM strikers can use.

-Marian Swerdlow, New York City