Why Are They Shutting Down a Chicago Emergency Room During a Pandemic?

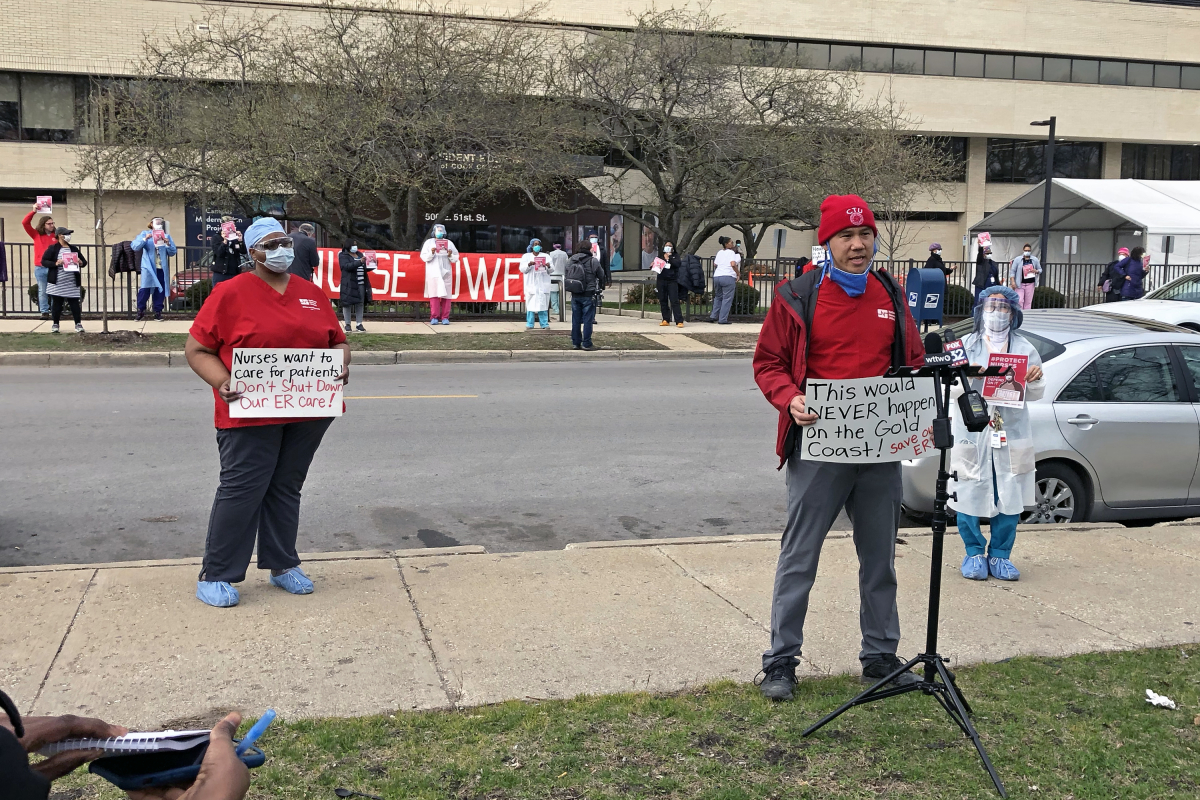

National Nurses United (NNU) held a rally to demand answers about why the emergency room of a public hospital in the heart of Chicago’s mostly Black South Side is being closed down for a month, just as the coronavirus pandemic is surging. Photo: Alan Maass

The emergency room of a public hospital in the heart of Chicago’s mostly Black South Side is being closed down for a month by Cook County officials, just as the coronavirus pandemic is surging in Chicago. The nonsensical justification is that the ER needs to be refitted to handle… a surging coronavirus pandemic.

Nurses and staff at Provident Hospital first learned by email last Friday afternoon that the ER would be closed as of Monday morning, April 6. As for notifying the community, county officials left that to a press release.

National Nurses United (NNU) held a press conference and rally during the Monday afternoon shift change to demand some answers from the Cook County Health System, which runs the hospital on the south end of the Bronzeville neighborhood.

“They say they want to make the emergency room safer,” said Dennis Kosuth, who works shifts in the ER in addition to his job as a nurse in the Chicago Public Schools. “We agree with that—it should be safer. But you don't do it by sending an announcement out on Friday that the ER is going to close on Monday.”

BLACK CHICAGOANS DYING

So far Chicago has trailed other pandemic hot spots like New York City and Detroit in its number of cases, but the curve started rising fast last week. Last weekend also brought the horrifying news that African Americans, who make up just over 30 percent of Chicago’s population, made up nearly 70 percent of its COVID-19 deaths. Black Chicagoans are dying from COVID at a rate six times higher than whites.

If the pandemic takes the course it has in other cities, South Side neighborhoods like Bronzeville will be devastated in the coming weeks.

Officials say the Provident ER needs to be renovated to ensure that staff can isolate COVID-19 sufferers and maintain social distancing during their care. But NNU said in a statement that the county has known this since it began preparing for a crisis in January. Yet it gave less than three days’ notice of its “solution” to staff—and to the community, effectively none at all.

There was no consultation with the health care workers who know the hospital best. Nurses said they would have pointed out that there is space in Provident to temporarily relocate emergency services.

“There's an alternative, and that’s to open up the rest of the hospital for the ER and bring in more medical staff,” said Rigo Gomez at the rally. He’s a local resident who brings his parents—both undocumented immigrants who rely on the public health system—for care at Provident.

“We need more, we don’t need less,” Gomez said. “What we see in the disparities in who dies and who survives are policies like this that are taking away the few resources we have.”

“Just up the street from here, they’re dumping $13 million into McCormick Place,” said Kosuth, referring to the much-publicized makeover of a giant convention center to add 500 more beds for COVID patients. “They have 400 workers there, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, to convert that place into a hospital. Why can’t they do the same thing down here at Provident?”

STROGER STRAINED TOO

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Managers of the health system say that people served by the Bronzeville hospital can rely on emergency services at other hospitals, including the city’s main public health facility, John H. Stroger Hospital, west of downtown. But many Provident patients are walkups, say nurses, and Stroger is a 20-minute drive away.

Plus, Stroger is already strained by the pandemic. Elizabeth Lalasz, a medical-surgical nurse at Stroger and an NNU member—who has been in quarantine after testing positive for COVID and coming down with symptoms two weeks ago—said the main county hospital is overwhelmed, its critical care unit almost entirely filled with severe COVID cases.

“People are struggling to keep up,” she said. “And the staffing is so bad, not only because some nurses have come down with COVID, but because people are experiencing PTSD. It’s that bad. Hospital nurses are pretty hardcore, but nurses are calling the union saying they’re having anxiety attacks on their way to work.”

Lalasz said management tried on Sunday to pull ER nurses into the critical care unit because of shortages. “You can’t do that,” she said. “ER nurses aren’t trained in critical care. But this is happening all over the hospital—they’re trying to shove people into specialties that they’re not trained for.”

The ER nurses pushed back against the reassignment. “We said, ‘Give us training right now, and compensation, because there’s a premium for critical care,’ and they backed off,” Lalasz said. “But here’s the problem—by the time the p.m. shift came on, eight nurses had called off, and so there were three nurses for 21 patients in critical care.” The usual ratio is one nurse to two patients.

LIVES CUT 30 YEARS SHORT

The dire conditions at Stoger and the temporary closure of the Provident ER both illustrate the stark inequalities of the health care system in one of the richest cities in the world.

Shocking as it is, the highly disproportionate COVID death toll among Black Chicagoans can’t truly be a surprise in what was already the U.S. city with the biggest life expectancy gap between its neighborhoods.

According to a 2019 report by the New York University School of Medicine, residents of Near North Side Streeterville, with its luxury lakefront condominiums and high-end retail stores, live to be 90 years old on average—while nine miles away, life expectancy in the poverty-stricken, nearly all-Black neighborhood of Englewood is just 60.

Provident nurses are angry at the double standard. “You couldn't imagine them doing something like this at Illinois Masonic up in Lincoln Park [on the North Side],” Kosuth said. “There's no way that the people of Lincoln Park would tolerate Masonic putting out an email to staff on Friday saying: ‘Oh, by the way, the emergency department is no longer going to be open on Monday morning.’”

Alan Maass is a labor journalist based in Chicago.