Book Review: The Politics of Immigration

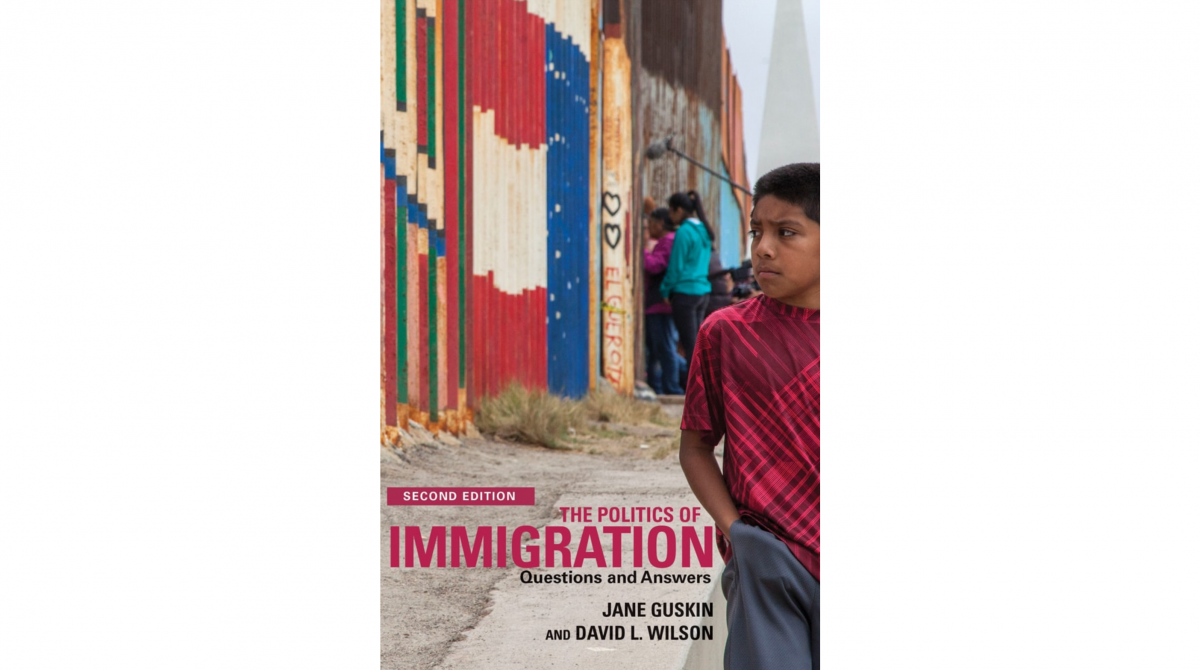

The Politics of Immigration, Questions and Answers (2nd Edition) by Jane Guskin and David L. Wilson. Monthly Review Press, 371 pp.

After Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officials terrorized undocumented workers by raiding 7-Elevens nationwide last month, and with 800,000 federal workers’ jobs on temporary shutdown over the status of the Dreamers, now’s a good time to take a look at how U.S. immigration policies affect the workplace.

Immigration law and enforcement in the U.S. are cruel, unjust, and expensive. Detained immigrants—even when they have committed no crime, merely a civil violation—are treated worse than felons. For instance, roughly two-thirds do not get lawyers. Parents are torn from their children. People detained at the border are kept in frigid holding cells, despite the fact that exposure to extreme cold has been judicially determined to be torture. And the cost to taxpayers is billions of dollars per year.

Meanwhile the lie flourishes that immigrants worsen U.S. jobs. The reality is more complex. When undocumented workers agitate for better working conditions or pay, their bosses hold a trump card to quash their organizing—the threat of deportation (though such threats are illegal). But their vulnerability puts downward pressure on everyone’s pay. This could be resolved with a broad amnesty program for undocumented workers.

WHY NOT OPEN BORDERS?

Closed borders are a new phenomenon, as Jane Guskin and David Wilson, journalists who work for immigrant and labor rights, detail in the newly released, second edition of their book The Politics of Immigration. “Many nations, including the United States until the twentieth century,” the authors write, “have maintained their laws, their form of government and their national identity, while leaving their borders more or less open.” In the U.S. that began to change in the 1920s, and really accelerated after 1940.

The alternative is what we have now—an undocumented underclass, living in fear, afraid to report a crime because contact with the police could lead to deportation, and often afraid to report wage theft for the same reason.

This book counters the stereotype of the tax-avoiding, social service-abusing, job-stealing immigrants with facts. For instance, in 2005, the Social Security Administration assumed “that about 75 percent of unauthorized immigrants… were paying the same income, Social Security and Medicare taxes as other workers.”

But, the authors write, “the proportion later shrank as the government cracked down on people… using false documents to work on the books.” So that was the thoughtless and unintended consequence of a thoughtless crackdown—decreased tax revenue. As of 2013, 56 percent of undocumented workers were employed off the books, according to the book. Even so, the authors cite New York Daily News columnist Albor Ruiz’s point that “‘corporate giants’ often pay less in taxes than the undocumented.”

They note that even the conservative Alexis de Tocqueville Institution concluded in 1994 that “the evidence suggests that immigrants create at least as many jobs as they take [by purchasing goods and services], and their presence should not be feared by U.S. workers.”

ROOT CAUSES OF MIGRATION

In the section entitled “How can we address the root causes of immigration?” the authors answer: “by supporting worker and union movements,” in the U.S. and internationally.

Unfortunately for many Central Americans, the U.S. government’s “policies cause exactly the sort of economic hardships that lead people to migrate,” the authors report. Under NAFTA, “more than 1.5 million Mexican farmers… had to sell or abandon their farms.”

Over and over the U.S. has supported right-wing foreign regimes that oppress populations and destroy economies, sending people fleeing—to the U.S. For instance, after right-wing military officers overthrew Haiti’s popular President Jean Bertrand Aristide in 1991 and U.S.-backed paramilitaries began murdering his supporters, the crisis sparked huge Haitian migration to here.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Some immigrants have been favored over others: Cubans fleeing communism were allowed into the U.S. en masse, while Guatemalans escaping U.S.-backed death squads in the 1980s were not.

Since 2014 the U.S. has seen a spike in the number of unaccompanied children crossing the border, fleeing violence in Mexico, El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. The 1980s wars and the 1990s economic policies “contributed to high poverty and crime rates in Central America,” the authors explain.

Honduras has the highest murder rate in the world of any country not at war. And yet, “despite evidence of links between security forces and drug gangs,” the authors note, “the Honduran military continues to get millions in U.S. aid.” Indeed, the U.S. government supported the 2009 right-wing coup against a moderately liberal president, whose main crime appears to have been raising the minimum wage and supporting unions.

Double standards abound. The book describes how the asylum process in the U.S. is biased in favor of the wealthy. There’s even a special category of visa for millionaire investors.

WORKERS SUFFER

Meanwhile, “undocumented workers appear to have a far higher rate of fatal injuries on the job than other workers.”

The situation is even worse for “guest-workers,” whom employers import on special visas. The authors dig into the guest-worker program’s eye-opening history. In Florida in 1942, we learn, “the U.S. Sugar corporation was indicted for conspiracy to enslave African American workers. The next year the sugar companies started using guest-worker programs to bring cane cutters from the British West Indies.” No wonder the authors refer to the guest-worker program as “this slave labor program.”

The book documents campaigns by the Farm Labor Organizing Committee to boycott corporations for abuses and to obtain contracts and union representation for guest-workers. Though these can be dangerous efforts—one union organizer, sent to Mexico to educate workers about guest worker jobs in the U.S., was murdered in 2007—there have been successes too. The authors cite the 2004 Farm Labor Organizing Committee agreements with “the North Carolina Growers Association and the Mount Olive Pickle Company, settling a five-year boycott and extending union representation.”

The Politics of Immigration also raises questions about the operations of immigration control. While ICE is supposed to release vulnerable people, often it jails them in detention cells instead. Who are these vulnerable people? “Torture survivors, lesbian, gay and transgender immigrants, pregnant women, children travelling alone, parents with children, people with intellectual disabilities and mental illness.”

This book offers illuminating context on immigration issues. It also provides useful talking points, facts and figures for chatting up anti-immigrant co-workers.

Eve Ottenberg is a journalist, novelist, and long-time teachers union member.