Pete Seeger’s Grains of Sand

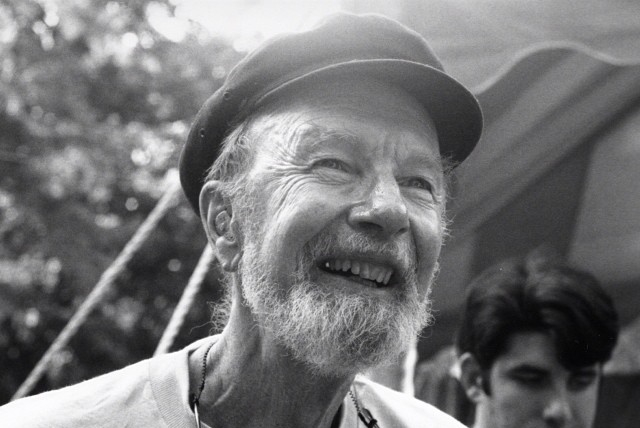

Most of us wind up narrowly focused on our own little corner of the movement. But Seeger’s philosophy was the opposite: he planted little seeds everywhere he went. Photo: Devan Goldstein.

“I’m a read-aholic and a magazine-aholic,” Pete Seeger told Amy Goodman on Democracy Now! in 2004. “I read music magazines, environmental magazines, union magazines, civil rights magazines.” We’re proud that Labor Notes was among them.

The great folksinger-activist, who died January 27 at age 94, was a subscriber since 1992 and a donor.

Seeger stood by labor all his days. “If you want higher wages, let me tell you what to do: you got to talk to the workers in the shop with you,” begins a wonderful, funny talking blues that Seeger’s group, the Almanac Singers, wrote in 1941 to boost CIO organizing.

When he was hauled before the House Un-American Activities Committee, he told HUAC’s lawyer, “I am proud of the fact that my songs seem to cut across and find perhaps a unifying thing, basic humanity.

“I know many beautiful songs from your home county, Carbon, and Monroe, and I hitchhiked through there and stayed in the homes of miners.”

He learned “We Will Overcome” in 1946 from labor educator Zilphia Horton at the Highlander Folk School. She’d learned it from striking tobacco workers in South Carolina.

Another Highlander educator, Septima Clark, changed “will” to “shall”—a better vowel for singing—and that’s the way Seeger taught Guy Carawan, who taught the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. “We Shall Overcome” became the civil rights movement’s most famous hymn.

Seeger assumed tobacco workers had made up the song. Much later he found out striking mineworkers had sung “We Will Overcome” in 1908—calling it “that good old song” even then.

Folksingers call this roundabout route “the folk process.” Organizing often works this way too.

SOME SEEDS SPROUT

Most of us wind up narrowly focused on our own little corner of the movement. But Seeger’s philosophy was the opposite: he planted little seeds everywhere he went.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

“There’s a wonderful parable in the New Testament,” he explained to Goodman. “The sower scatters seeds… Some fall on the rocks, and they don’t grow.

“But some seeds fall on fallow ground, and they grow and multiply a thousandfold. Who knows where some good little thing that you’ve done may bring results years later that you never dreamed of.”

For example: When Pete was invited to play the 1997 Northwest Folklife Festival, he asked for a labor chorus to back him up.

That’s how the Seattle Labor Chorus was born. They’re still going strong, brightening many a picket line and union meeting. If you come to the Labor Notes Conference, you’ll hear them.

LITTLE TEASPOONS

Seeger’s great antiwar song “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy” was censored from TV’s Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour in 1967. But after public outcry it aired to 7 million viewers.

Shortly after, President Johnson announced he wouldn’t run for re-election—a sign the tide was turning against the Vietnam War.

Of course, Seeger didn’t claim “Waist Deep in the Big Muddy” made LBJ back down. Not alone, anyway. “The song would be probably just one more thing,” he said. “I honestly believe that the future is going to be millions of little things saving us.

“I imagine a big seesaw, and one end of this seesaw is on the ground with a basket half-full of big rocks in it. The other end is up in the air. It’s got a basket one-quarter full of sand. And some of us got teaspoons, and we’re trying to fill up sand…

“One of these years, you’ll see that whole seesaw go zooop in the other direction. And people will say, ‘Gee, how did it happen so suddenly?’ Us and all our little teaspoons.”