Kroger Workers Vote Down Contract in Indiana by 74 Percent

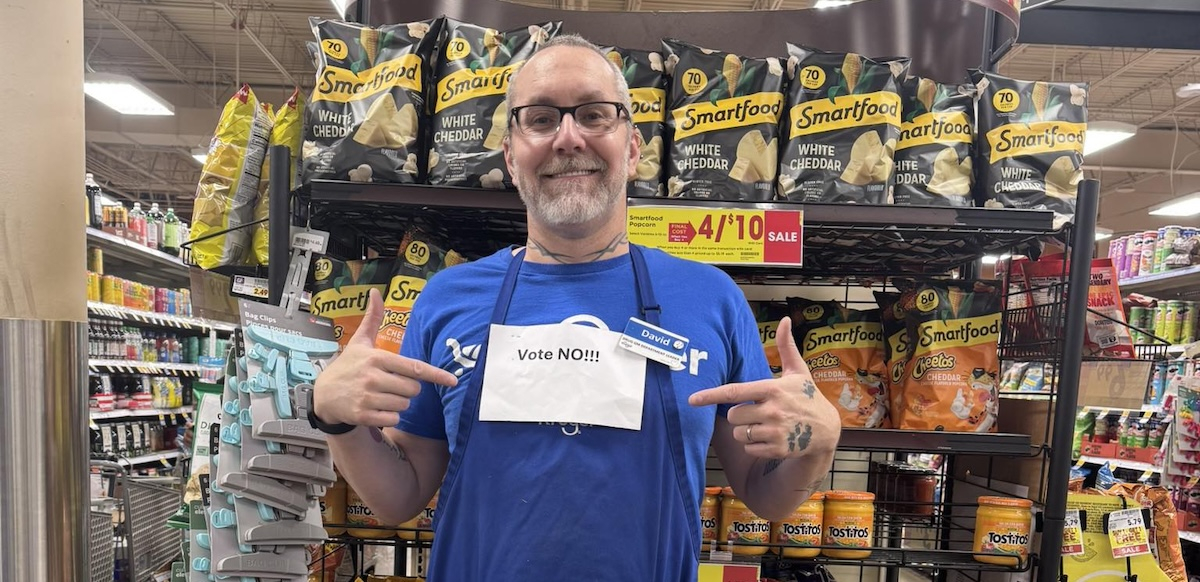

David Fredrick displays his home-made “Vote No” sign at an Indianapolis Kroger. Union members voted down a proposed contract by 74 percent, covering 8,000 workers. Photo courtesy David Fredrick.

Food and Commercial Workers (UFCW) Local 700 members in Indiana voted down a tentative agreement May 31 covering 8,000 Kroger retail workers, with 74 percent voting no. Rank-and-file members bucked the recommendation for a ‘Yes’ vote by local union leadership and the bargaining committee.

The tentative agreement includes wage increases of 50 cents over four years for some job classifications, while the first pay step would receive a 75 cent bump. Both the first and second pay steps would see a 25 cent raise in the first year.

“With inflation, our wages are backsliding,” said Amy Reynolds, a 24-year Kroger worker in Fishers, near Indianapolis. “You wonder if you can make it on a job like this. When my mom worked at Kroger in 1970, her wages were comparable to the UAW Chrysler plant. Today, we’re nowhere close.”

The contract also includes changes to seniority language so that only full-time employees gain seniority rights. Approximately 70 percent of workers across Kroger’s retail division are part-time.

If the contract had passed, “my part-time co-workers would probably have to start looking for new jobs,” said Tari Blevins, a front-end cashier in Indianapolis.

For grocery workers who worked through COVID like Blevins, the tentative agreement felt like a slap in the face. “During COVID, we had million dollar [sales] weeks,” Blevins said. “We had customers fighting in the aisles over product.”

NO STAFFING HELP

Despite national attention on chronic staffing issues in Kroger stores—including a recent investigation from Consumer Reports on how understaffing results in higher prices for customers—the Indiana contract saw no improvements on staffing.

“Corporate decided we only need one cashier between 10 and 11 p.m.,” Blevins recalled. “For almost a year, it was not unusual for me to have between 30 and 50 people in my self-scan line at night when I closed.”

“We didn’t get a single win,” said Alexander Schalk, a shop steward at a Kroger grocery store in Bloomington. “Top rate will be permanently blocked off, so everyone is effectively taking a pay cut. The one thing touted as a major win was spousal insurance, but that doesn’t start until 2029. It made me angry enough to start organizing about it.”

Schalk, Blevins, and others talked to their co-workers about voting no on the contract. They distributed flyers at their home stores and neighboring stores providing information about the contract, with a QR code linked to a Zoom meeting for members to get together and discuss next steps. They made sure co-workers knew when, where, and how to vote. They messaged in Facebook group chats when they had voted, and kept each other updated on how votes were going in their own stores.

RIGHT TO WORK (FOR LESS)

Members of UFCW Local 700 face an additional challenge: statewide “right-to-work” laws. Few Kroger stores in the local have more than 70 percent membership. A vicious cycle is produced: bargaining leverage is weakened by lower union membership, and weaker contracts can fail to demonstrate to workers the true power of a union.

“I’ve talked to about a dozen people who told me if the [contract] was passed as is, they planned on quitting the union,” said Schalk. “Ideally, this would be the time to show people exactly what the union is for. A contract should be a great time to get people involved.”

However, some members had the opposite reaction. “There were several people who signed up for the union because they wanted to vote no on the contract,” Schalk said. In a Facebook group for Kroger workers, one member mentioned getting three new members signed up for the union while organizing for a no vote.

“SECRECY ISN’T STRENGTH”

Members had just two days to review the contract before voting began on May 30. Voting took place in hour-long slots at each store, twice a day for two days. “If I was trying to minimize voter turnout, this is the method I would take,” said Schalk.

This is the second time in three years members have voted down a contract proposal; in June 2022, members voted down their first tentative agreement by 51 percent. One month later, an updated tentative agreement passed by 60 percent, with minimal changes aside from a lump-sum signing bonus for employees at the top of the pay scale.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

“There’s a lot of ways to scare people into voting yes, like telling them we won’t have enough money in the strike fund if we strike,” Reynolds said. “What they [union leadership] don’t mention is that some people tried to change that at the 2023 Convention, and they opposed it.”

“It’s the same old story—there’s a culture of secrecy,” said Reynolds. “I was on the bargaining committee in 2012, the year that spousal coverage was taken away. We were told not to talk about anything. I felt like a fraud.”

“In no way, shape, or form is secrecy a strength,” Reynolds continued. “It gives the power to the company. The members need to lead. This is our union.”

Reynolds suggested that open bargaining could help. “We see other locals doing it, like Teamsters Local 135 here in Indiana, or UFCW Local 7 in Colorado. It takes work. But it allows members to take control.”

COORDINATION GROWING

The Local 700 contract would have extended the length of the collective bargaining agreement from the current three years to four years, putting them out of phase with over 150,000 other workers at the same employer. Currently, most UFCW contracts are bargained local by local. Although there are more than 700,000 UFCW members at Kroger and Albertsons-owned grocery stores nationwide, the UFCW lacks a national master agreement or large-scale coordinated bargaining.

However, more UFCW locals are trending towards greater coordination to boost leverage at the negotiating table. In the first two weeks of June, approximately 60,000 members are voting simultaneously to authorize strikes at Kroger and Albertsons-owned stores in UFCW Locals 7 in Colorado, Locals 135, 324, 770, and 1167 in Southern California, and Local 3000 in Washington. It’s the largest coordinated strike authorization vote in UFCW history.

Kroger has been responding by demanding longer contracts in order to stymie coordination. “It would be nice if we could coordinate more,” Schalk said. “This contract is trying to put us on a 4 year cycle, which would put us out of sync.”

Independent efforts from members through groups like Essential Workers for Democracy have encouraged national coordination by bringing rank-and-file bargaining committee members to attend one another’s bargaining sessions.

Members in Indiana are still fighting for a fair contract. “What people want is a decent raise of at least $3 or $4 over the life of the contract,” said Schalk. “I want to encourage people to stand up.”

Caitlyn Clark is a national organizer at Essential Workers for Democracy (www.ew4d.org), an organization dedicated to rank and file member education and empowerment for workers in grocery, meatpacking, and retail.