How Oakland Teachers Took Control of Our Return to School

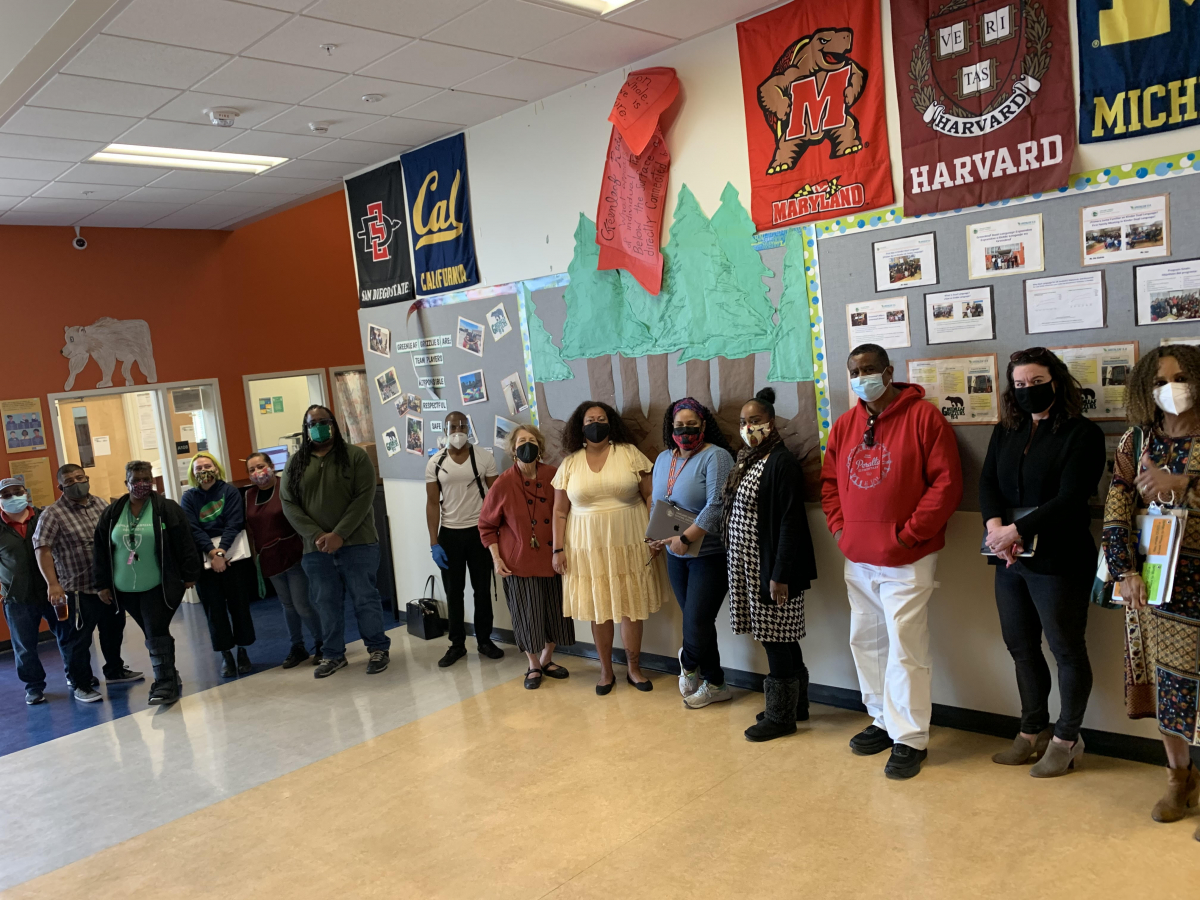

After the Oakland Education Association bargained an agreement on a plan to reopen Oakland schools this spring, the union decided on an ambitious plan to conduct union-led safety walkthroughs at over 100 schools and early childhood education centers within three weeks. Photo courtesy of authors.

A union contract isn’t worth the paper it’s written on if it isn’t enforced. And our boss has a spotty record when it comes to honoring agreements.

So after we bargained an agreement on a plan to reopen Oakland schools, we decided on an ambitious plan to conduct union-led safety walkthroughs at over 100 schools and early childhood education centers within three weeks.

AN OFFER THEY COULDN’T REFUSE

It was March when, with declining Covid case rates and expanding access to vaccinations, the Oakland Education Association’s Big Bargaining Team reached an agreement to end the school year in Oakland with in-person learning for small cohorts of students. A week later, our members ratified the agreement in a close vote.

We had insisted on—and won—robust safety measures that exceeded state and federal guidelines: social distancing, small and stable cohorts of students, ventilation, health screening, universal face coverings, handwashing, personal protective equipment, and enough time for all school staff to be vaccinated before students returned.

Our legal right to inspect workplaces for safety is ironclad in California. But with buildings still mostly empty at that point, we wouldn’t be able to conduct walkthroughs without the employer’s cooperation to have somebody unlock the doors and let us in.

So we made the boss an offer they couldn’t refuse. At the first school board meeting after we reached an agreement, our union president publicly invited the board members to join us as we conducted safety walkthroughs at every single school before students returned.

The optics of interfering with our rights would have been a public relations disaster far worse than any unfair labor practice award.

100 SITES IN A SHORT TIME

Making the pledge publicly also held us accountable to follow through on what amounted to a lot of work in a short amount of time.

We started by looking at public health data and identifying the schools that were in the neighborhoods with the highest ongoing Covid case rates. We made these schools our first priority.

Together with school workers represented by SEIU and AFSCME we developed a one-page checklist, in plain language, of safety measures to look for at every school.

Safety experts from our statewide union—including an infectious disease doctor and a mechanical engineer—reviewed our materials for accuracy.

We then trained our union stewards over Zoom on the safety measures in our agreement, how to conduct a safety walkthrough at their school, and where to turn for help, if needed. Nearly one in 10 union members is a shop steward or other elected leader in our union, giving us strong worksite coverage.

We used a Google Form for reporting at the end of each walkthrough and provided regular updates to union leaders and shop stewards.

Union officers and staff joined nearly every walkthrough at schools in the hardest-hit neighborhoods. Union stewards largely handled walkthroughs at the remaining sites in Oakland.

Where possible, school board members, parents, other union leaders, and central office administrators joined us too.

“It helped to create an environment of trust and collective problem solving as we embarked upon what was, for some, a scary endeavor—reopening our school during Covid,” said Carrie Anderson, an elementary teacher. “Folks got to ask questions and have conversations about what was happening, the ways in which we were ready, weren’t ready, and what the plans were to fix what needed fixing before the kids arrived.”

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

“People felt more agency knowing what they could enforce because the expectations were really clear and had been made so public,” said Vilma Serrano, a transitional kindergarten teacher.

By conducting these safety walkthroughs, we soon realized that our contract language for safe ventilation was too vague. Covid is airborne and our students’ simple cloth masks wouldn’t filter aerosols, so this was a big concern for us.

We quickly reached an understanding with the Employer to provide a minimum of four air changes per hour (ACH) through HEPA filtration in each classroom and shared workspace.

We then recorded a training video with the chief steward of the Building Trades Council explaining the science behind the proper use of portable HEPA filters.

We also published a straightforward chart showing how many portable HEPA filters would be needed to achieve four air changes per hour in different sizes of classrooms.

OUR EYES AND EARS

Overall, we found that most sites were prepared with the safety measures we had won at the bargaining table.

The data we collected allowed us to identify which schools had safety issues that could be resolved by shop stewards and which sites needed additional support from leadership.

With the safety walkthroughs largely complete, rank-and-file educators formed the next layer of enforcement. Many returned to buildings several days ahead of our students.

Our Big Bargaining Team—18 members, including a district nurse—conducted dozens of site meetings (virtually) to educate members on safety measures, instructional schedules, and leave policies. We also encouraged all of our members to attend safety webinars presented by our statewide union.

That gave the union eyes and ears nearly everywhere, on alert for safety concerns.

TOOK CONTROL OF THE PROCESS

Returning to in-person learning during a pandemic was never going to happen without some level of risk. But rather than waiting for the boss to follow through on promises to keep us safe, we took control of the process.

Writing our own safety checklist and inspecting worksites ourselves allowed us to ensure the safest possible teaching and learning conditions for our schools.

Approximately one-third of Oakland’s students opted to return in-person during the spring. Although students and staff tested positive for Covid after the reopening, there were no known in-school transmission between students or staff.

Looking beyond the pandemic, we’ve learned a new approach to systematically setting standards in all of our schools. We plan to conduct more mini-campaigns in the future to ensure that Oakland’s students are learning in buildings that are safe, clean, and welcoming.

Shelby Ziesing is a second-grade teacher in Oakland. John Green works for the Oakland Education Association.