How to Beat Retaliation, Even without a Union

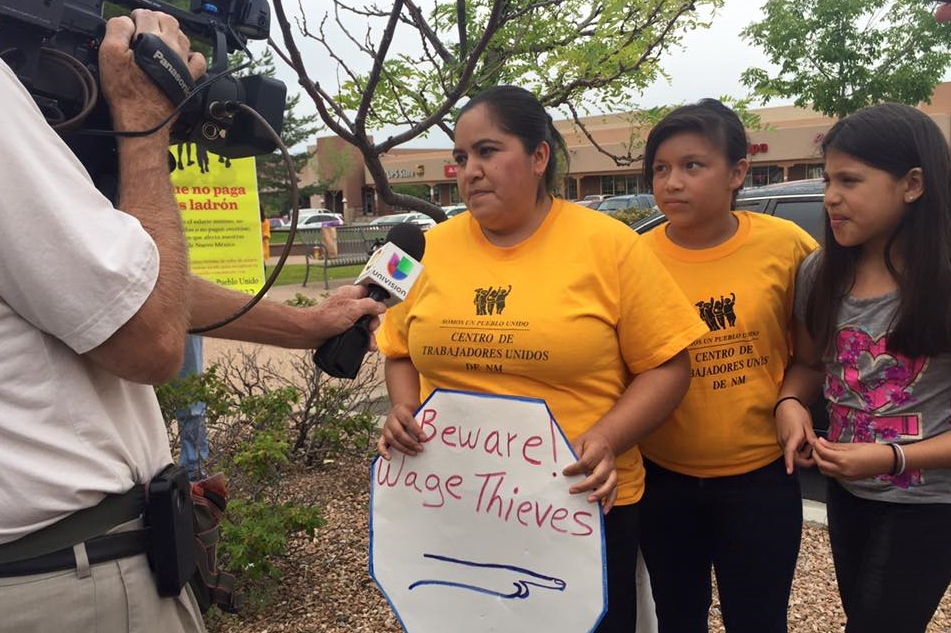

Somos un Pueblo Unido, a New Mexico worker center, is honing a process to help even tiny groups of workers win changes through small collective actions—while staving off retaliation. Photo: Somos un Pueblo Unido

When you’re working without a union, it can feel impossible to take on workplace problems. What if you lose your job?

But Somos un Pueblo Unido, a New Mexico worker center, is honing a process to help even tiny groups of workers win changes through small collective actions—while staving off retaliation.

Willing co-workers form a committee, agree on a plan, and commit to share the risks. Somos helps them tailor their plan to maximize the protection they’ll get from federal law and from community publicity.

Carlos Campos had worked at a Santa Fe restaurant for seven years when he formed a committee with two co-workers. The others in their workplace of 29 were nervous about joining. Some were single mothers who couldn’t take the risk.

In the past, when they’d brought up working conditions, the boss would tell them, “the door’s wide open and you can leave,” says Campos. “We knew we had to organize ourselves.”

The group’s first public action was to hand their boss a letter, asking the restaurant to start paying for overtime, respect their lunch breaks, and stop requiring them to attend a monthly meeting without pay.

The restaurant fired all three. But that wasn’t the end of their organizing—just the beginning.

GETTING PAST FEAR

Concerted Activity:

The Best-Kept Secret

How did Campos and his co-workers get legal protection?

Under Section 7 of the National Labor Relations Act, workers in most industries—whether they’re union members or not—have the right to carry out “concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection.”

Concerted activity usually means two or more employees are acting together to try to improve pay and working conditions, but recent decisions have applied the definition even to one worker acting on behalf of a group.

If workers face retaliation, the NLRB can order their employer to “restore what was unlawfully taken away.”

“We think the right to engage in protected concerted activity is one of the best kept secrets of the National Labor Relations Act, and more important than ever in these difficult economic times,” wrote NLRB Chairman Mark Gaston Pearce in 2012.

With the help of Somos, the workers did two things right away: they filed a National Labor Relations Board complaint, and they organized a loud demonstration in front of the restaurant—a story that was picked up by local media.

In four months, Campos was back at work. The NLRB had ordered the employer to reinstate him and his co-workers, and to reimburse all lost wages.

The restaurant also started providing lunch breaks, and ended the unpaid meetings and overtime.

“Fear will always be there, and employers take advantage of this,” says Campos. “But we have rights and we deserve respect.”

This group faced the worst retaliation a boss can dish out. But more often Somos is finding that employers, recognizing their legal position, don’t retaliate at all.

Testing the waters with action can be a swift way to boost workers’ confidence and get results on the job.

MAKING RIGHTS REAL

Somos un Pueblo Unido didn’t start out with a focus on workplace organizing. The organization, which is celebrating its 20th anniversary, has an impressive track record of legislative successes.

Through community mobilizing and lobbying it won a living wage in Sante Fe, stronger wage theft protections, and a state law granting licenses to undocumented workers.

But despite winning new rights on paper, Somos members kept seeing them violated in practice.

“We had amazing members who were incredibly skilled at creating strategies, talking to media, and doing policy work, but at the end of the day were still incredibly vulnerable in the workplace,” says Executive Director Marcela Diaz. “That contradiction was too much to bear for our members.”

In 2008, when 14 women were fired at a Hilton hotel—after demanding a meeting with their manager about harsh chemicals and the excessive number of rooms they were expected to clean—Somos helped them file complaints with the NLRB, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, and the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

Somos had supported many workers to file individual OSHA and wage complaints in the past. “We never saw a strong effort to get folks reinstated,” Diaz said. “Legally people are protected against retaliation, but practically they are not protected.”

But this was the first time the group had appealed to the NLRB. The employer ended up agreeing to pay back wages and post a notice in the workplace listing the violations.

Somos learned a lot through this first case. “We started asking, ‘What if we engaged proactively in protecting concerted activity?’” said Diaz.

Over the last five years, the organization has supported the formation of 50 workplace committees at hotels, restaurants, car washes, landscapers, and cleaning companies.

“We didn’t set out to create a model,” says Diaz. “When you don’t have the power to bargain, you have to be creative. We throw mud at the wall to see what sticks—and this is what stuck.”

THE SOMOS MODEL

What Protects Somos’s Workplace Committees?

The letter to the boss, signed by at least two workers, bolsters a legal defense against retaliation. If workers are fired, they have clear documentation that they took part in collective action and the boss knew about it.

A rally immediately after any retaliation draws publicity the boss doesn’t want, and shows that the workers have community backing. Somos makes clear it will keep up the public pressure. Other employers see what they’ll face if they choose to retaliate, too.

Filing an NLRB complaint against retaliation, in Somos’s experience, has usually won reinstatement or back pay—through either a board decision or a negotiated settlement. As the group’s record of victories grows, employers can see that a legal fight isn’t worth the expense.

When workers contact Somos with a problem, organizers start by helping them understand their rights.

“Violations tend to cluster,” says Diaz. “If an employer is willing to steal wages from an employee, usually there are other workplace violations.”

The next step is to ask if it’s happening to other people. It usually is. Somos helps workers to recruit co-workers and organize a meeting, where representatives from other worker committees come and share their experiences.

That’s often when people start to get excited, says Diaz. The workers talk about what they’d like to change, and lay out the steps for applying this model in their own workplace.

Next they put their demands in writing. Often the letter to the company includes a warning that the workers will file an EEOC, wage, or OSHA complaint if conditions don’t change. Workers always ask the employer to meet and discuss their concerns.

Somos asks committee members to sign a contract with the organization—and each other—that establishes some basic rules.

Workers agree they won’t meet with the employer alone, and they won’t sign anything without checking with the others. If the committee is forced to file a complaint, the contract states how members will distribute any settlement monies within the group.

All committee members must agree to speak to the media about their complaints. “If no one knows about this, we’re not building power,” says Diaz.

Once the letter is delivered, the employer will know workers are organizing. Somos stresses that workers must not give the employer any excuse to retaliate.

Workers roleplay how the boss may react to the letter. For example, what if the employer offers to meet with just one committee member?

After the letter delivery, in many cases workers see changes on the job right away. “They feel like it’s that letter that protects them,” Diaz says.

FIGHTING RETALIATION

Going public about violations is another critical part of the strategy.

If an employer retaliates, workers organize an immediate public demonstration, where they’re joined by community allies and members of other workplace committees.

Somos encourages local media, including Spanish-language newspapers, to cover these protests. In a small community like Santa Fe, word travels fast.

Enough cases have been publicized now that “employers know not to retaliate,” says Diaz. “They know what’s going to happen if they do.”

So far there’s been severe retaliation, like firings, in only 12 of the 50 cases. Many times workers don’t need to file an official NLRB complaint at all, because employers address workers’ demands— from getting safety equipment to wage increases—and don’t retaliate.

The cases that do go forward often end with settlements or board decisions that require employers to reinstate workers or pay back wages. Not all cases are resolved quickly, though. In one case, it took five years for workers to win, because their employer kept appealing.

What about when a case involves undocumented workers?

Undocumented workers are protected under the NLRA and many other workplace laws, and have the same rights to concerted activity as other workers. Immigration status cannot be raised until the very last stage of a NLRB complaint. But the Supreme Court’s Hoffman Plastic Compounds decision does limit their access to key remedies—reinstatement and back pay.

In the vast majority of cases, Diaz says, questions of status haven’t come up. When employers have tried raising it, workers still won, through settlements.

RIPPLE EFFECT

Diaz is quick to point out there are limits to what a workplace committee can achieve. Without a recognized union, an employer doesn’t have to sit down and negotiate with workers.

But when a union drive might not succeed—for instance, because workers can only recruit a small minority willing to participate, or the workplace is too small to interest a union, or it has high turnover, or it’s full of temporary workers—this is a tool they can still use to make changes.

Through the experience, members develop skills that also feed into Somos’s ongoing policy campaigns on racial profiling, wage theft, and immigration reform.

Some committees continue to meet once the issue is resolved. Others come together again to strategize if new problems emerge. Other workers often look to committee members for advice or support.

Campos didn’t stay long at the restaurant job after being reinstated. He says the boss found other ways to make the environment difficult. But he’s proud that he changed his workplace for the better—and started a ripple effect by fighting publicly.

“People who are in the same situation could see that it’s possible to make a change at work,” Campos said. “That motivates other workers to do the same.”

“It builds an incredible solidarity and camaraderie,” says Diaz, “that is invaluable to a workers’ organization and workers’ rights movement in a place as small as Santa Fe.”