How Auto Parts Workers Shut Their Plant

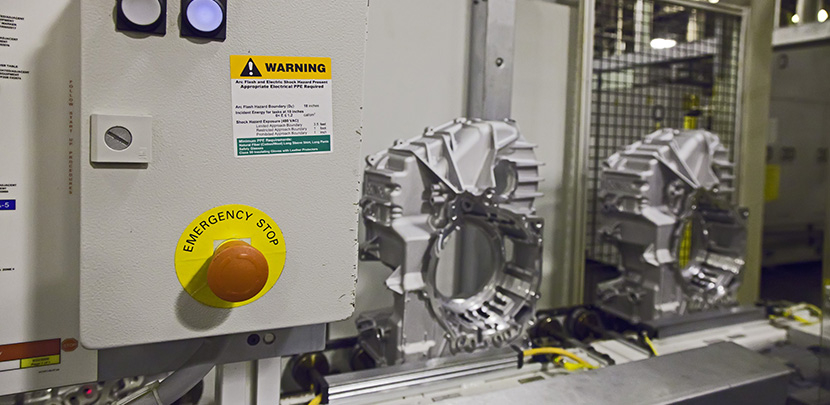

An "emergency stop" button in a transmission plant. Photo: Jim West, jimwestphoto.com.

Union members at a Detroit-area auto parts plant refused to work March 19 and 20 after learning that a management employee had tested positive for the coronavirus. Angry first-shift workers gathered outside the plant and refused to enter.

The story is a textbook example of management indifference and worker solidarity. “It was one of those moments I am proud to be in a union,” said union chairman Trent DeSenglau. “This solidified us for sure. I have never seen so much support ever.”

The plant in Fraser, Michigan, near Detroit, belongs to American Axle and supplies the Big 3 automakers with axles and transmission parts. Its 145 workers normally work three shifts, seven days. “We are like a social experiment,” DeSenglau said, “every race, every religion, every sex, gay people, straight people, what a union should be. And everybody was united over this.” With overtime, average pay is about $55,000 a year.

They are one unit of a big United Auto Workers Local, 155, that has 53 different contracts. When Michigan went “right-to-work” in 2011, the unit lost only two members. And when DeSenglau was elected chairman six years ago, he got them back.

As coronavirus fears ramped up this month, the union was developing a plan on how to keep members safe. Late in the day March 18, management informed union leaders that it was canceling second shift—but wouldn’t say why.

“Eventually we got it out of them that somebody had tested positive,” DeSenglau said. “We didn’t even know people were being tested. They had sent out a few people to be tested, all management people.

“The person who tested positive, his job was ‘continuous improvement.’ He goes around to every area and tries to improve it, which he does every day. It’s basically how much we can get out of the employee for as little money as possible. He’s right next to people while they’re doing their job, he’s asking questions.”

Management didn’t ask any hourly workers whether they had come in contact with any of the infected people. Instead they just looked at the sick people’s calendars on their computers. DeSenglau said he had been in a meeting for two-and-a-half hours with one of those who tested positive. “They didn’t ask any union people at all if they were in any interactions with these guys,” he said. “How were you supposed to know who should be quarantined?”

TWO STANDOFFS

A cleaning company was called in and second and third shifts were canceled that day, but management gave workers no reason. Workers informed each other, though, and when first shift, about 65 workers, showed up the next morning, “nobody wanted to work,” DeSenglau said. “We had basically a standoff in front of our plant. I didn’t want them entering the building till we had this figured out.”

DeSenglau and another local officer interposed themselves between workers and managers to avoid a physical fight. A corporate HR person emerged, and told workers that if they were concerned, they could go home and stay off for a week.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

But she wasn’t expecting the response: 90 percent left. And on the second shift, only two worked. On third shift, zero.

CORPORATE CHANGE OF MIND

On finding out that no one would work unless forced, management changed its corporate mind. “They weren’t counting on that,” said DeSenglau. “They make an offer, they don’t like the outcome, so they change the offer. That’s what they do.”

So management started contacting workers at home and ordering everyone to show up the next day.

Once again the first shift came to work, for another standoff outside. “This is bullshit, you lied to us,” workers yelled. No one went in. When workers gathered for the second shift, a plant-level HR person came outside, and caved.

That was a Friday. On Monday Governor Gretchen Whitmer ordered all nonessential workplaces shut down. The plant's customers—Ford, GM, and Fiat-Chrysler—had already been shut down since the previous Wednesday.

All along the American Axle unit had the backing of Local 155 officers and the UAW regional office. “It was ‘do what we needed to do,’” DeSenglau said.

UNEMPLOYMENT MESS

To put icing on the cake, management then proceeded to mess up workers’ unemployment benefits. They had filed individually, but then, without telling anyone, management filed for the whole workforce, creating chaos and confusion. People’s claims were closed and dates were changed. DeSenglau found out when he got a letter from the state agency.

Still, workers are 100 percent glad they did what they did, DeSenglau said. “Most of the time you have issues and some people feel one way, some another. With this it was a solidifying moment, it unified everybody.

“It comes down to just act like a human being. Money isn’t everything. With everybody’s differences we can all agree on that.”