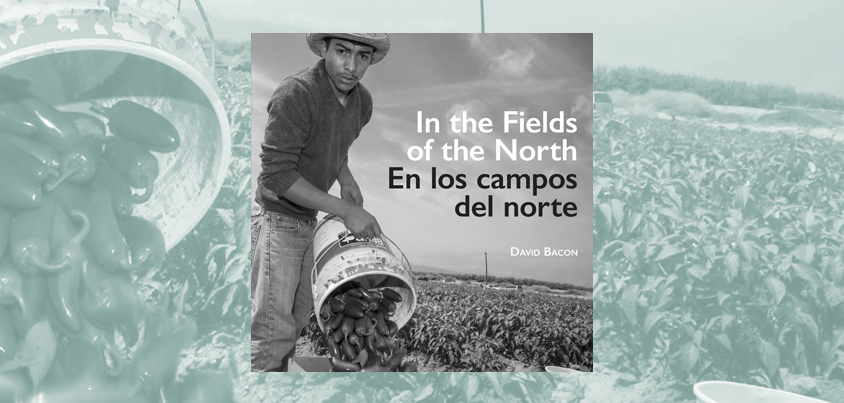

Review: In the Fields of the North (En los campos del norte)

David Bacon’s unforgettable new English-Spanish photo-essay, In the Fields of the North (En los campos del norte), is about migrant farm workers on the West Coast. Bacon says that without unions, the state of affairs in the fruit and vegetable fields would be even sorrier.

Mexican blueberry picker Honesto Silva Ibarra died in Washington state on Sunday after complaining of headaches but being forced by his supervisor to return to work in the blazing sun. He ended up in a coma. When 70 of his co-workers struck Sarbanand Farms to protest Silva's treatment, they were fired the next day and within an hour were thrown out of their company-owned housing.

Such situations are typical of those found in David Bacon’s remarkable new English-Spanish photo-essay, In the Fields of the North (En los campos del norte), about migrant farm workers on the West Coast. The main takeaway from the book is that if the United Farm Workers were a stronger union, tragedies like this would not occur. But it should also be said that without the UFW and smaller independent unions like Familias Unidas por la Justicia (Families United for Justice), the state of affairs in the fruit and vegetable fields of the West would be even sorrier.

Still, most farm workers don’t have a union yet, and many of those who do have not had a contract for a long time.

WORTH A THOUSAND WORDS

This book contains unforgettable photographs. There is one of farm workers from the Gallo ranch in Sonoma Valley, who “cross arms, hold hands and sing at the end of a meeting to protest the unwillingness of the company to sign a union contract. Holding hands and singing at the end of a meeting is part of the culture of the United Farm Workers.”

And these workers, mainly indigenous people from Mexico, have lots to protest. As Lucrecia Camacho recalls: “I would tie my young children to a stake in the dirt while I worked and I tried to work very fast, so that the foreman would give me an opportunity to nurse my child…I’ve always been alone, a single mother of ten children…The strawberry harvest…[is] hard. I don’t wish that kind of work on my worst enemy.”

The labor is arduous, the living conditions atrocious: workers describe how they sleep out in the open, under trees or tarps. Explaining what led to one strike in Washington, Rosario Ventura says: “We were upset about the conditions in the labor camp. The mattress they gave us was torn and dirty, and the wire was coming out and poked us…There were cockroaches and rats. The roof leaked when it rained…All my children’s clothes were wet.”

Eventually, because of the strike, the company agreed to some of the workers’ demands.

The photographs of the shacks, tents, trailers, and tarps the workers live in and under are powerful—the need for decent housing everywhere evident. These hovels often stand right next to luxurious upper-middle-class abodes, separated only by a low wall or path. “We’re the first trailer park to have the owners legally removed,” says Elisa Guevara, who leads Mexican farm workers protesting bad living conditions. “When people realize they don’t have to be quiet and afraid, then change will happen.”

PARTISAN ART

As Laura Velasco Ortiz writes in the book's afterword, David Bacon is a “partisan artist.” He himself elaborates: “Eighty years ago, many photographers were political activists and saw their work intimately connected to worker strikes, political revolution or the movements for indigenous peoples’ rights…I don’t claim to be an unbiased observer. I’m on the side of immigrant workers and unions in the United States.” His new book highlights resistance and solidarity, but it also exposes injustice and details the exploitation of the people who put food on our tables.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Today growers are “paying an illegal [subminimum] wage to tens of thousands of farm workers,” Bacon says. Workers get about $1.50 for picking a flat of strawberries. “Each flat contains about eight plastic clamshell boxes, so a worker is paid about 20 cents to fill each one. That same box sells in a supermarket for three dollars…If the price of a clamshell box increased by five cents (a suggestion made by the UFW during the Watsonville strawberry organizing drive of the late 1990s), the wages of workers would increase by 25 percent.”

Workers are thus cheated of a fair wage. They are also threatened with deportation, if they complain, and they have no work in winter. But coming from 13 Mexican states, they speak 23 languages and have strong community ties. As Bacon points out, these bonds are key to their efforts to organize.

Romulo Muñoz Vazquez recalls: “I was beaten at work five years ago on a ranch by the freeway in San Diego. The boss asked us why we weren’t working hard. I told him we weren’t animals and we had rights. I still remember everything they did to me afterwards...On May Day we’ve decided not to go to work…We must organize ourselves in order to move ahead.”

LIVE, NOT JUST SURVIVE

Most migrants crossing the border today are, typically, about 20 years old. In the chapter, “I'm Going to Be a Rapper with a Conscience,” Raymundo Guzman, a young farm worker from Oaxaca who lives in a trailer in Fresno, explains: “I really didn’t like to work in the fields when I was in school. I still don’t like it, but we have to do it.”

He speaks Mixteco, Spanish, and English. “I graduated from high school,” he says. “I was the first in my family to do it, my mother was so proud that she threw me a party…but I felt sad…because I didn’t know what to do with my diploma, I didn’t know where to go and nobody at school helped me.” He describes picking grapes in the dizzying heat, and the pain in his knees and back from bending over to pick strawberries all day. “I want to live, not just survive,” says Guzman.

Farm workers have difficulty just getting decent clean water. Arsenic contaminates the drinking water of migrants in Lanare, California, an issue around which residents have organized. Another problem is rampant sexual abuse at work and gender discrimination in hiring. But job insecurity remains one of the biggest issues.

“I know one [foreman] who only hires immigrants without papers, because she says legal residents complain too much,” Lucrecia Camacho reports. “It’s always based on if they like you or not, we just have to put our heads down and work quietly.” Speaking of the cost of living, she goes on: “The more we earn, they more they take away. We can’t move forward…if I didn’t work fast, I was fired immediately.”

Everyone in this book who is asked thinks a union would help. “When I was working for [the UFW],” says Andres Cruz, leader of a Triqui immigrant farm worker community, “a group of workers…told me that the company they worked for was firing people every day, this company wanted each worker to pick 250 pounds of peas daily…their hands were so swollen and cut…Sometimes organizing a strike takes three to four days, but in some cases, we can organize in one day…When [our community decides] to do something collectively, they are very united.”

That is why the work of the UFW and of smaller independent unions is vital. (After many strikes, Familias Unidas por la Justicia ratified a first contract this summer with Sakuma Bros. Berry Farms in Washington.) So are groups like California Rural Legal Assistance and indigenous movements like La Nación Purepecha. And so are publications like In the Fields of the North.