Pension Theft Crime Wave

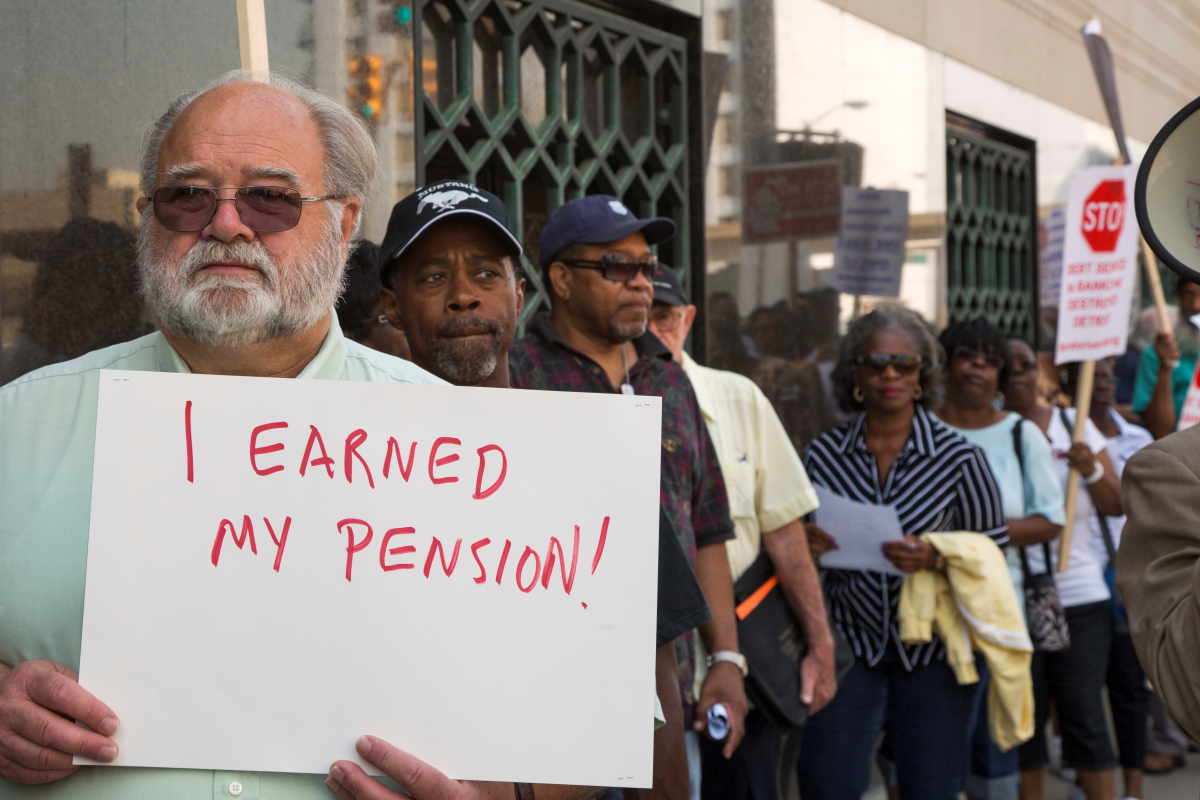

Detroit declared bankruptcy in July, giving the appointed “emergency manager” a chance to wreck pensions. Photo: Jim West/jimwestphoto.com.

The nation’s union-haters have a juicy new target, Detroit’s public employees, ever since the city became the largest in history to file for bankruptcy. Detroit unions will wrangle with a bankruptcy judge this fall over how to handle $3.5 billion in pension obligations for 12,000 retirees.

City retirees receive a princely sum of $19,213 per year on average. Pension obligations to these workers account for less than 20 percent of Detroit’s debt. But the facts haven’t kept retirees from bearing the brunt of the bankruptcy fallout.

In fact, politicians across the country are seizing on Detroit’s hard times as an excuse to trim public pensions closer to home. For them—and for bankers angling for a piece of the action—this could be the breakthrough they’ve been waiting for.

Lawmakers from both parties have climbed onto the same noisy bandwagon as right-wingers who complain that public pensions are too fat, ballooning out of control because of unions run amok. They throw in the fact that retirees are living longer, and tout the soon-to-be swollen ranks of retiring baby boomers, to add some statistical cover to their judgments and finger-pointing.

MANUFACTURED CRISIS

But the fact is that the crisis in funding for pensions, both private and public, is a manufactured one. It’s rooted in the Enron-style accounting and “something-for-nothing” financial engineering that set off the 2008 financial meltdown.

Making wishful assumptions about future stock market performance, corporate execs shortchanged pensions, diverting dollars into outsized dividends and stratospheric bonuses for themselves. Many were long gone by the time the bill came due.

The same dynamic drove politicians—hardwired to tell people what they want to hear—to claim that sure, corporations and the rich could have tax cuts while public sector workers continued to receive their pensions and regular raises.

Now that state and local governments are swimming in red ink because of those tax cuts and the Wall Street meltdown, unions are caught flat-footed. Their erstwhile allies, after testing today’s political winds, now line up to ax their pay and pensions.

Rhode Island drew the road map for politicians everywhere two years ago, slashing state and municipal workers’ pensions with a brutal “reform” that forced most workers over to a hybrid plan and froze cost-of-living adjustments.

The brunt fell on retirees like 19-year firefighter Paul St. George, whose $36,000-a-year pension turned into $24,000 overnight. He had to move out of his house into an apartment and find full-time work as a maintenance man, he told the press.

UNCOMFORTABLE ARITHMETIC

Adding insult to injury, the state handed more than $1 billion in pension funds over to hedge fund companies to manage—in exchange for an expected $2.1 billion in fees over 20 years, effectively taken straight out of the pockets of retirees, who would forego $2.3 billion in COLAs over the same period.

No wonder Wall Street has pumped $2 million into the possible gubernatorial campaign of Gina Raimondo, who engineered the Rhode Island scam, as Matt Taibbi recently reported for Rolling Stone.

Even before the 2008 financial crisis and the gaping holes it created in state and local budgets, pensions were an endangered species. In 1980, 40 percent of the workforce had traditional defined-benefit pensions. Today it’s less than half that.

Corporations drove this shift—axing retirement plans altogether when they could get away with it, switching to 401(k) plans where they couldn’t. These programs were legalized in 1978 and were originally designed to supplement traditional pensions. But 401(k)s quickly provided a cheap escape route, costing companies about half as much as traditional pensions. Even more important, 401(k)s shifted risk off companies and onto us.

Traditional pensions were a stab at a collective solution to a universal problem—how to lead a decent life when your working years were through. Pooling retirement savings among workers at a large company, or across an entire industry, smoothed out insecurity for everyone. Now it’s just you and the stock market.

The research shows you’ll end up with far less in your pocket. A 401(k) typically yields 10 to 33 percent as much as a traditional pension. Half of all participants between the ages of 55 and 64 have less than $120,000 in their 401(k)s.

PRIVATE SECTOR PLAYBOOK

For union members in the private sector, today’s attacks on public sector pensions have a familiar ring. Corporations spent years gaming the defined-benefit pension system in a similar pattern: First, siphon off pension contributions to pump up profits—as simple as tweaking the company spreadsheet to reflect a rosier forecast of your investment returns.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Then, once the accounting gimmicks are played out, howl about legacy costs, declare bankruptcy, and stick someone else with the bill.

Companies from steel giant LTV to Twinkie-maker Hostess have followed this pattern. And things have gone from bad to worse in the five years since Wall Street’s collapse.

At the end of 2012, private sector defined-benefit plans had only about 75 percent of what they owed participants. Shortfalls this year could swell to as much as $322 billion—up from $47 billion at the end of 2007—according to the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation.

The PBGC, a government agency established in 1975 to backstop private sector pensions, is funded by premiums paid by healthy plans, along with assets recovered from bankrupt companies. But swamped today with failing plans, the agency is operating in the red. Last year the deficit between its income and its obligations swelled to a record $35 billion.

Even before the red ink, the PBGC’s payouts typically amounted to less than half of what retirees were promised by their employers. Republic Steel is an egregious example: workers watched their pensions get cut by up to $1,000 a month in 2002 when the PBGC took over, then get cut again in 2004.

In the second round, some retirees saw their benefits fall as low as $125 a month.

The PBGC’s bulging deficits could trigger even more cuts to payouts, with Washington in no mood for any emergency appropriations.

For workers in multi-employer pension plans like the Teamsters’ ailing Central States Fund, pending federal legislation would permit preemptive cuts even without PBGC involvement (see Stealth Bill Would Allow Cuts to Current Pensions).

ONE-TWO PUNCH

Though 80 percent of public employees still have traditional pensions, more and more politicians are reading from the private sector playbook. After skipping payments into their pension funds repeatedly during better economic times, when the funds looked flush, now they are pushing for deep cuts.

“The numbers speak for themselves—the pension system as we know it is unsustainable,” Andrew Cuomo insisted after his election as governor of New York.

Cuomo, like politicians across the political spectrum, has pitted public employees and their unions against taxpayers—while the corporations and 1%ers who benefited from decades of tax cuts quietly slip out of the spotlight.

With two-thirds of public sector pensions facing shortfalls—to the tune of $700 billion in 2010—these attacks from politicians are gaining traction.

New York, one of 10 states to push through major changes to pensions last year, added a sixth tier for new hires in its state plan. Other states took similarly severe measures, such as dropping traditional pensions for new employees in favor of defined-contribution plans, increasing age and service requirements for retirement, and jacking up employee contributions. Alabama took the controversial step of terminating its traditional pension plan.

Far from shoring up our faltering retirement system, these measures will only increase its fragmentation, putting each small slice of the population into a different leaky boat.

As unions fight to defend members’ pensions, it’s worth thinking beyond our shrinking share of the workforce to measures that will benefit everyone. For half the country’s workers, Social Security is already all they have. And on the flip side, some or all public employees in 15 states don’t get Social Security, so their pensions are all they have.

What if we took seriously the fate of retirees, and strengthened Social Security so that it could actually pay for most living expenses? Whether your retirement was golden or tinfoil would not depend on the health of your particular employer—a radical proposition, to be sure.

We’re a long way from a universal retirement plan that robust. Cutting Social Security is almost a bipartisan goal now. So the first step is to stop politicians from hacking at Social Security as part of a “grand bargain” on the debt ceiling, Obamacare, future government shutdowns, or anything else.