Denied Collective Bargaining, North Carolina Public Employees Turn More Militant

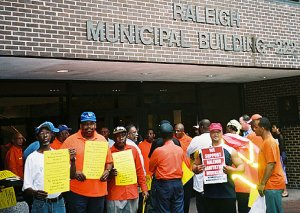

Sanitation workers in Raleigh, North Carolina had had enough. For two days in September, they staged work stoppages for several hours each day, refusing to move their trucks off the garage lot.

More than 50 workers participated in the strike, delaying pickups of garbage, recycling, and yard waste across Raleigh’s growing sanitation routes in protest of forced overtime, lack of pay for overtime worked, expanding routes with a reduced workforce, and harassment by supervisors.

The strike came in the wake of United Electrical Workers (UE) Local 150’s campaign to organize municipal workers across North Carolina, from Charlotte to Greenville and from Chapel Hill to Fayetteville.

Chapel Hill’s transit and other town workers joined UE Local 150 in 2005 and went before the town council demanding redress for the lack of full-time pay for bus drivers working 14 to 16 hour days. They also demanded a process for working out other workplace issues. This resulted in the initiation of “meet and confer” (non-binding collective bargaining) with town managers and the eventual firing of the transit department director.

Charlotte city workers, beginning with the sanitation department, also joined Local 150 in 2005 and staged a protest of nearly 100 workers during a Charlotte city council meeting. The protestors demanded that the council address unbearably long hours for sanitation workers, disrespect and racism in the workplace, and understaffing. They also demanded meet and confer rights with city managers.

Durham sanitation workers, long-time members of Local 150, also staged two small work stoppages in 2006, protesting the lack of holiday pay when workers were forced to work some holidays.

COMMUNITY SOLIDARITY

One of the most remarkable aspects of the Raleigh strike was the amount of support and solidarity the workers received from the Raleigh community.

Student volunteers drove trucks with loudspeakers through the streets of Raleigh, calling on the community to support the sanitation workers’ demands and to “fight the power.” Community residents posted signs in their yards declaring, “We Support Raleigh Sanitation Workers Demands for Justice.”

Newspaper articles featured interviews with Raleigh residents from across the city who supported the workers, recognizing their difficult work.

Citizens packed Raleigh city council meetings as the workers presented their chapter of Local 150 to the city and called for collective bargaining. The demand for collective bargaining, illegal for public sector workers in North Carolina, paved the way for the mayor to agree to meet and confer negotiations.

BARGAINING RIGHTS

For several years, UE has been building a movement to demand repeal of General Statute (GS) 95-98, the North Carolina law prohibiting collective bargaining for public workers. Organizing these workers statewide and building the movement for collective bargaining remain the center of UE’s work in North Carolina.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

In 2002, UE 150 helped launch the HOPE (Hear Our Public Employees) Coalition, a statewide coalition of unions and labor organizations demanding repeal of 95-98. Local 150 is one of the eight core decision-making groups that make up the heart of HOPE today.

In 2004, UE launched the International Worker Justice Campaign (IWJC) as its official offensive to win collective bargaining rights for public sector workers. The IWJC has been one of the key forces behind the growing social solidarity with labor that was demonstrated during the Raleigh sanitation workers’ strike.

In 2004 and 2005, the IWJC organized a series of public hearings where public sector workers from universities, hospitals, social service institutions, and city, county, or state government bodies testified before community leaders, ministers, and elected officials about working conditions.

To build public awareness, the IWJC held press conferences, organized rallies and “sticker days” at work, and distributed bulletins and fliers around the state. In the fall of 2006, the IWJC worked closely with Local 150’s executive board to organize a series of community forums across the state calling for the right to collective bargaining for public sector workers.

As a result of these and other efforts, the North Carolina State NAACP has come out in full support of the repeal of GS 95-98. The newly formed Faith, Labor, and Community Alliance, a south-wide organization of churches and religious leaders that support workers’ rights, has also made the call for collective bargaining and the repeal of GS 95-98 a pillar of its work.

INTERNATIONAL STANDARDS

The UE has appealed to four international bodies under the rubric of labor standards that are widely recognized and established internationally under human rights law.

The International Commission for Labor Rights (ICLR), a network of jurists experienced in international law, published a report in 2006 documenting North Carolina’s violations of international labor standards in denying public sector workers collective bargaining rights.

UE has also made a formal complaint about North Carolina’s denial of collective bargaining rights to the International Labor Organization (ILO), a body of the United Nations. The ILO’s decision is still pending and should be announced later this year.

In October 2005, Mexican unions, working with the UE, filed a formal complaint under NAFTA’s side labor agreement, NAALC, charging North Carolina and the U.S. of violating labor standards established under the NAALC by denying collective bargaining.

In early January the UE appealed to the Organization of American States’ (OAS) Inter-American Commission for Human Rights for a hearing to determine whether North Carolina’s denial of collective bargaining violates of OAS labor standards.

Ashaki Binta is the coordinator of the UE International Worker Justice Campaign and a long-time leader of Black Workers for Justice.