Wage Gains at UPS Have Amazon Workers Demanding More

Teamsters from six different locals joined newly-unionized Amazon delivery drivers from California in picketing an Amazon warehouse in northern New Jersey July 6. The Teamsters tentative agreement with UPS is inspiring demands among Amazon workers. Photo: Teamsters.

Amazon warehouse worker Paul Blundell has spent the past year talking to his co-workers about how UPS Teamsters were getting organized to strike. So recently, he had big news to share: “A few days before the strike deadline, UPS caved.”

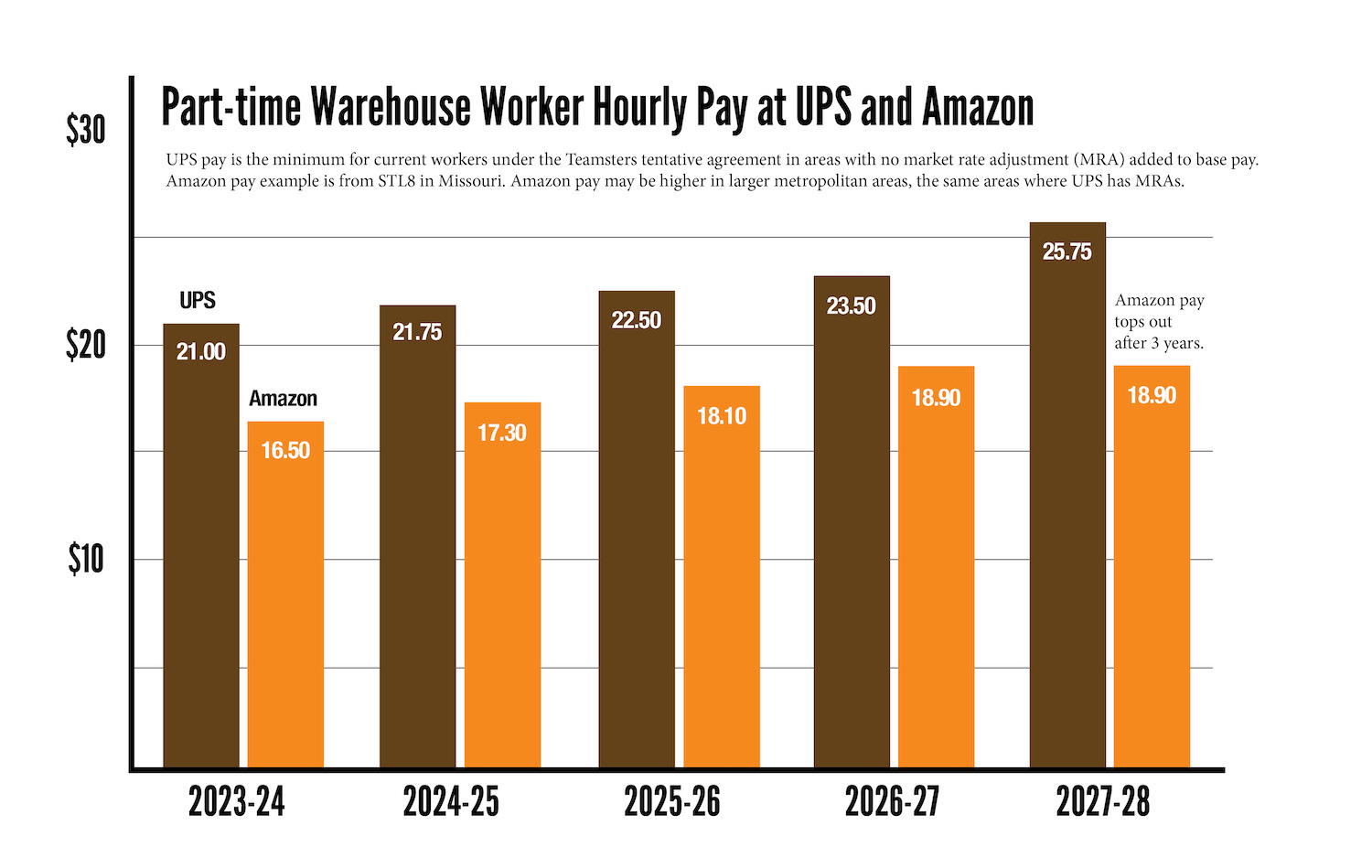

“Everybody’s jaw dropped” when they heard that night shift workers at the Philly UPS air hub will get an immediate raise to $24.75, Blundell said. “We top out around $20.90 after three years, so UPS is now starting well above that—with raises for the rest of the contract.”

UPS part-timers also have low-deductible health insurance coverage with no premiums, and pensions.

At UPS’s Philadelphia air hub, the current wage for an inside worker starts at $20 an hour for the day shift and $22 for night. In South Jersey, an inside worker starts at $19.75 on days.

UPS Teamsters are voting August 3-22 on whether to ratify the tentative agreement. But the big wage gains made at the negotiating table are already reverberating at Amazon, where the company is slated to adjust its wage progression in the fall, and workers are hoping to make the case that they are underpaid compared to their peers at UPS.

NOTICEABLE DIFFERENCE

Amazon employs a million workers in the U.S. across 1,300 warehouses, and pays a patchwork of wages.

At the JFK8 fulfillment center on Staten Island, New York, part-timer David-Desyrée Sherwood saw the boost in pay at UPS as something to organize around. “The $21-an-hour starting wage is crazy strong compared to what we make at Amazon,” he said.

“I know part-timers at UPS wanted more, but I still think it’s a noticeable enough difference for us to agitate around, plus their wage progression is also infinitely better than what Amazon gives us.” He later added: “I support whatever the rank and file votes to do.”

He said at JFK8, full-timers start at $18.75 and are capped at $21.75 after three years; part-timers earn the same wages but are on a different progression.

JFK8, where workers won a union authorization election last year, offers the most competitive Amazon wages in the region. Presumably union density in the borough pushes up wages; the average wage on Staten Island is $41 per hour and the median household income is $85,381, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

At RDU1, an Amazon fulfillment center just outside Raleigh, North Carolina, Reverend Ryan Brown welcomed news of the tentative deal.

“It shows the power of solidarity, the threat of a strike, and collective bargaining,” he said by text message. “We hope that the Teamsters have the same success in organizing Amazon delivery stations.” Brown is president of Carolina Amazonians United for Solidarity and Empowerment (CAUSE), the independent union of Amazon workers at RDU1.

At the 3,000-worker fulfillment center STL8 in St. Peters, Missouri, Paul Irving and his co-workers struck Amazon last year on Black Friday (November 25) to demand higher wages, after marching on management in September to deliver a petition about wages and safety with 350 signatures. In response to the November strike, the company raised wages from $15.50 to $16.50 for part-timers but didn’t meet workers’ other demands, on safety.

But now, Irving and his co-workers are looking to make further gains. “If UPS wages go up, Amazon should do the same,” he said.

Workers at STL8 delivered another petition in April with 400 signatures. And they sent a letter in June to Amazon CEO Andy Jassy demanding that Amazon eliminate work practices that result in serious injuries.

RAISE THE STANDARD

Workers are taking on the e-commerce giant in one thousand cuts. In a growing unfair labor practice strike, Amazon delivery drivers from Palmdale, California, who joined the Teamsters have extended their picket lines to 10 warehouses in California, New Jersey, Connecticut, Massachusetts, Michigan, and Georgia.

At Amazon’s delivery station DGE9 in Buford, Georgia, 25 warehouse workers came out during their break to meet the Palmdale strikers while they were picketing a nearby Atlanta sortation center, ATL6.

In the parking lot, the workers had an impromptu conversation about shop floor organizing and legal protections that cover collective action.

“We had a real good conversation about our common struggles and what we can do about it,” said one of the delivery station workers, who asked to be anonymous for fear of retaliation.

Since then, the conversation has turned to the UPS contract. “The wages they won have sparked a lot of conversation,” the worker said, and the excitement is spreading to other nearby warehouses. “I just got off a call talking with other workers from Amazonians United Atlanta about trying to catch this lightning in a bottle right now.”

Last October, the Buford delivery station workers presented a petition and walked off demanding a base pay bump of $3, but they only got a 40-cent increase.

“The UPS workers have raised the standard, and we know that’s going to put pressure on Amazon from outside,” said Blundell in Philly. “But if we want to make the gains UPS workers have shown us can be made, we Amazon workers have to be organized from the inside to push this company to treat us with respect, with our wages, with our working conditions.”

FAIR PAY AND SAFE WORKLOADS

Blundell and his co-workers are campaigning across several warehouses in the Philadelphia metro area to demand that Amazon match what UPS Teamsters won, with the aim of taking this demand nationwide.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

“We do basically the same work,” he said. “There’s no reason we should be paid so much less by one of the richest companies in the world. If UPS workers had gone on strike, that message would have been shouted from the rooftops.”

They’re building on a petition that Amazonians United Mid-Atlantic piloted at the Philadelphia delivery station DDP9 and other facilities, demanding $22 an hour to match the pay rates at Target and Walmart distribution warehouses. Now they are expanding it to UPS ahead of Amazon’s annual announcement of its wage progression, known as the “step plan.”

The step plan allows Amazon to raise or lower starting wages. Because of the tight labor markets, workers say they’ve only seen wages go up, but they add they don’t know anyone who has been at the company long enough to remember further back than five years.

The petition also called for making overtime during peak season voluntary instead of mandatory, to reduce injuries from repetitive stress.

At a delivery station, workers load packages on trucks and vans on their way to the customer. The work involves lifting, carrying, twisting, and other strenuous repetitive tasks. Amazon has been cited many times for its failure to eliminate ergonomic hazards.

Workers also demanded in the older petition the right to listen to music while at work.

A PATCHWORK OF WAGES

Each Amazon warehouse has its own step plan. Some workers believe the company determines its wages based on an area’s cost of living; others say it’s based on an area’s median income.

“Ask management why and you’ll get all sorts of babble about ‘network standards’ and ‘target rates’ and ‘market assessments’ that amount to complicated ways of saying ‘because we can,’” according to a recent newsletter of Amazonians United Philly, the organizing network that Blundell and his co-workers work with.

On July 25, a warehouse worker in New Jersey’s fulfillment center ACY1 wrote on the company’s Voice of the Associates, an online bulletin board for Q&A with management:

“Congrats to UPS workers, who just fought UPS for a contract that raises wages by $2.75 immediately and by $7.50 by the end of the contract. Amazon’s step plan increases haven’t kept up with inflation for at least two years, we need a raise, too. Any plans for that?”

The head of Amazon’s human resource department responded, “As a former UPS employee, I am glad to hear UPS reached an agreement but I am prouder to work at Amazon,” and then chirped about flexibility.

“Amazon’s average starting wage in North America in fulfillment and transportation is $19, with employees earning between $16 and $26 per hour depending on their position and location in the U.S.,” said Sam Stephenson, an Amazon spokesperson. “Amazon reviews wages annually to ensure hourly pay is in line with what is being paid for comparable work locally.” The company wouldn’t clarify whether it was including the hourly rates of lower management in the average.

But Amazon’s starting pay at delivery stations in the Philly area is $17.80, according to a wage progression chart shared with Labor Notes. In Buford, Georgia, the starting pay is $17.20 with a 50 cent overnight differential. In Revere, Massachusetts, the starting pay at fulfillment center DMH9 is $17.75, with a three-year progression to $20.15. Amazon stops its raises after three years.

The only way to bump your wages beyond the steps is to become a “tier three worker,” such as a process assistant—a role that is adjacent to management but comes with no supervisory power. A process assistant at Amazon’s fulfillment center DMH9 tops out at $23; the same role at Staten Island’s JFK8 pays $24.65. Workers at JFK8 groused that Amazon’s failure to promote them into these roles was the catalyst that spurred them to unionize.

Amazon workers on Staten Island campaigned for a union demanding $30 an hour. Amazon drivers in California who unionized with the Teamsters won a $30 wage, but Amazon then canceled the contract of their nominal co-employer, Battle-Tested Strategies. At Amazon's Kentucky air hub, workers are demanding $30 an hour.

Some UPS part-timers already earn more than that. One of them is Elbie Lieb, a member of Teamsters for a Democratic Union and a part-timer with UPS in Indiana, who earns around $33 an hour after 27 years at the company. If the tentative agreement is ratified, her wages will be $42.29 by the end of the five-year contract.

UNION DIFFERENCE?

Blundell and his co-workers spoke with a Local 623 shop steward and other Teamsters so they could explain to their co-workers how UPS warehouse wages compared to Amazon’s in the Philadelphia and south New Jersey area.

For the Amazonians United Philly newsletter, workers put together a chart comparing pay across warehouses of non-union Walmart and Target as well as unionized workplaces like UPS and the Postal Service.

But the Teamsters’ existing contract didn’t show a compelling union difference.

This is partly because Amazon raised its minimum wage to $15 in 2018, in response to organizing and political pressure. UPS Teamsters had contract negotiations the same year, and the part-timers, who work in warehouses sorting parcels and loading them into delivery trucks, were pressing for a $15 starting wage.

But the union capitulated to a $13 starting rate, rising to $15.50 in 2022. Days after Amazon’s announcement, a majority of Teamsters voted down the tentative agreement, but Teamsters then-President James P. Hoffa imposed it anyway.

This year, with new leadership and stronger rank-and-file organization, UPS Teamsters have raised the wage floor substantially.

“Before deregulation, the International Brotherhood of Teamsters was the central force guiding competition in the logistics industries throughout the country, taking wages out of competition and forcing companies to compete on quality and efficiency,” said Brian Callaci, chief economist at the anti-monopoly Open Markets Institute and a former union organizer with UNITE HERE.

“The UPS contract is a huge win for UPS workers. But its potential significance is even greater: if it causes Amazon, FedEx, and other non-union workers to look at those gains and want that for themselves… Then maybe the union might be able to play that central role in the industry once again.”

“It's all one fight here in the logistics industry,” said Blundell. “We have to be organizing together. We have to be raising standards together, or we risk losing by being disorganized.”