Building on Dr. King's Legacy, North Carolina Municipal Workers Kick Off Bill of Rights Campaign

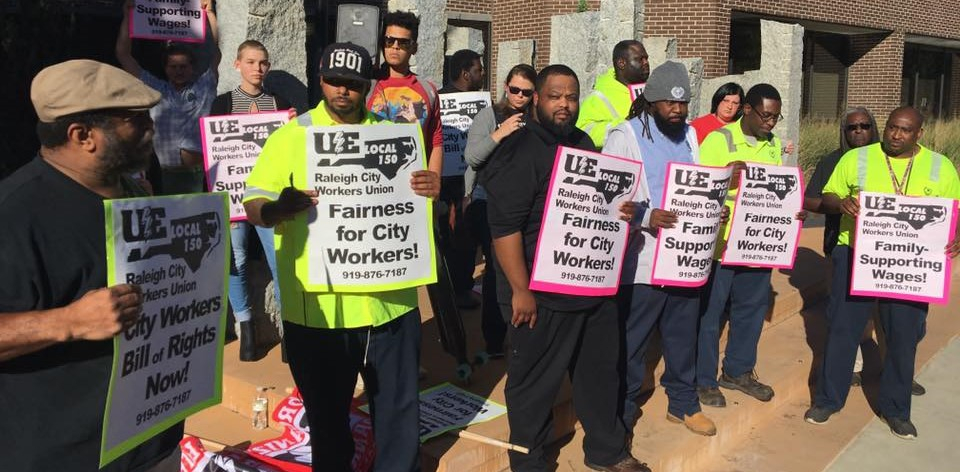

Fifty years after Martin Luther King, Jr., stood with striking Memphis sanitation workers who were fed up with low pay and dangerous conditions, UE Local 150 is launching a campaign in the same spirit. Photo: UE Local 150

A cold snap the first week of this year took a toll on North Carolina’s cities. In Greensboro alone, 38 water mains broke—and despite near-zero temperatures, municipal workers like Charles French were responsible for fixing them.

“We had workers out in frigid weather,” said French, a solid waste equipment operator. “We are the backbone of the city. Without us the city does not run.”

Yet North Carolina’s municipal workers say their work and their safety are undervalued by state and local governments. Fifty years after Martin Luther King, Jr., stood with striking Memphis sanitation workers who were fed up with low pay and dangerous conditions, United Electrical Workers (UE) Local 150 is launching a campaign in the same spirit.

The campaign kicks off on Martin Luther King Day with press conferences and rallies across the state. Members plan to spend the four months until the anniversary of Dr. King’s assassination April 4 building a statewide coalition to fight for higher wages, grievance protections, safety, and union rights.

North Carolina law prohibits collective bargaining for public sector workers. For a decade, Local 150 has been pushing to repeal it—and organizing municipal workers to fight for improved conditions even without bargaining rights. The union represents municipal workers in six cities and 11 municipal departments.

PRESSURING THE CITIES

As cities draft their yearly budgets this spring, UE Local 150 members will ask city councils to devote more resources to employees. The MLK campaign will highlight workers’ struggles for living wages and adequate health care, and the dangerous conditions they face on the job.

Long shifts in the summer heat can be as dangerous as the winter cold. Last summer Anthony Milledge, a laborer in the city of Charlotte’s yard-waste division, died of a heart attack after a sweltering 14-hour shift.

The strike that brought Dr. King to Memphis 50 years ago began after two sanitation workers were crushed to death in a garbage truck. Furious over the tragedy and the city’s longstanding neglect of the Black workforce, 1,300 walked out. Their signs said, “I Am a Man.” African Americans make up a big percentage of North Carolina municipal workers too.

After Milledge’s death last year, the union brought attention to the fact that no city in the state had a written policy to protect its own employees from excessive heat. Union members in Charlotte, Chapel Hill, Durham, Raleigh, and Greensboro organized rallies, passed out pamphlets, and held press conferences. Thanks to their efforts, many cities began drafting and implementing heat policies.

The campaign aims to establish statewide minimum standards for municipal working conditions. “City workers throughout the state face many of the same problems,” said Local 150 President Nathanette Mayo, a chemist with the City of Durham. “City administrators and managers typically come together to coordinate and track municipal work environments throughout the state. We believe that workers [too] should collaborate.”

WORKERS’ BILL OF RIGHTS

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Greensboro city workers are planning a January 16 press conference outside City Hall, just before a council meeting. They will ask for a $2,000-per-year raise across the board and a better grievance procedure.

The main problem with the grievance procedure is that workers are not represented, said French, the president of Local 150’s Greensboro branch. A worker who wants to raise a complaint has to go alone to meet with H.R. and management: “Going in the door, there’s really no one on our side.”

The union will also push the city to protect and compensate municipal workers who brave unsafe conditions, the way it already does for firefighters and police officers.

Union members in Charlotte, Raleigh, and Durham are asking for wage increases and better working conditions. They hope to lead the way for workers in smaller communities like Chapel Hill and Rocky Mount, where the union does not have as strong a presence.

In February the union will hold a statewide summit to draft a Municipal Workers’ Bill of Rights. Members want to push cities to maintain minimum standards for life-sustaining wages, health and safety, adequate staffing, fair grievance procedures, and more comprehensive health care.

A similar campaign in 2012 yielded some success. After the previous Bill of Rights stipulated that workers should be able to deduct union dues from their payroll and access public facilities during non-work times, these two provisions were mandated by North Carolina lawmakers. The union hopes to replicate such success this year.

COMMUNITY INVOLVEMENT

The union will call on churches, civic organizations, and local business leaders to help the campaign with such activities as leafleting, letter-writing, and petitioning. A number of these groups, including local NAACP chapters in Chapel Hill and Greensboro, will march with Local 150 on Martin Luther King Day. Allies can also sign up to be community supporting members of Local 150 with a $5 monthly donation.

French believes the campaign is easy to get behind. “Everyone wants to have their trash picked up, everyone wants to make sure they have water in their homes,” he said. “We just ask that you support and believe that we, as city workers, deserve what we’re asking for.”

Sarah Miles is a graduate worker at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill and a member of UE Local 150.