Why Did California's Tax the Rich Measure Lose?

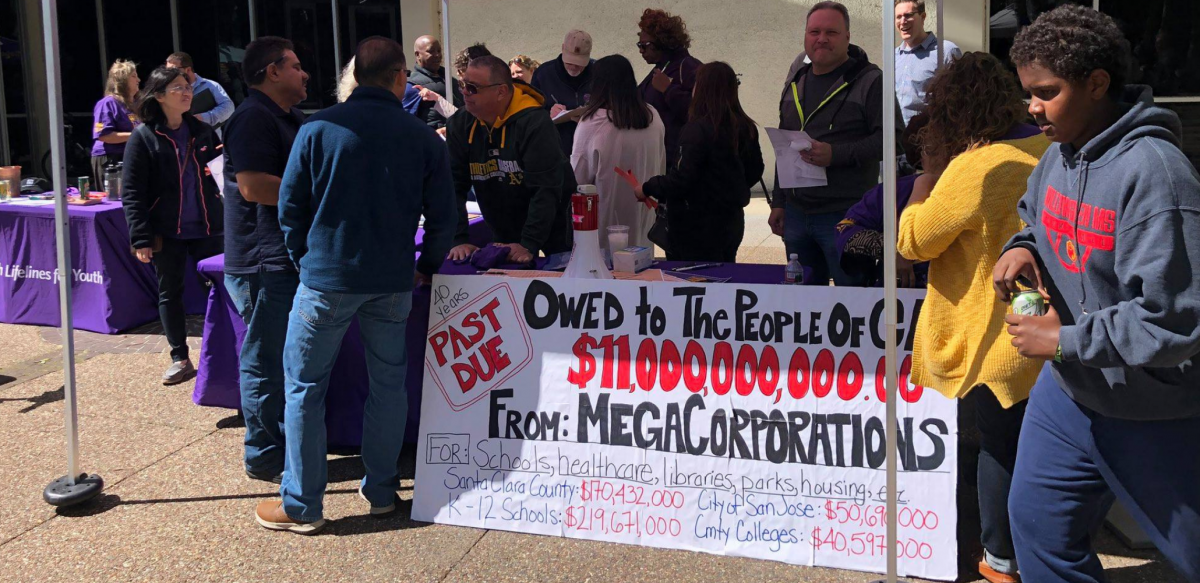

The Proposition 15 campaign emphasized the needs of public schools and local services and that big corporations and wealthy property owners should pay their fair share of taxes. Photo: Schools and Communities First.

California’s Proposition 15, a labor-backed progressive tax measure, gave up the ghost on November 10 after a weeklong vote count. The measure had proposed to close a corporate tax loophole worth $10 to $12 billion a year for schools and services.

The narrow (51.8-48.2) loss is somewhat surprising, given progressive tax victories in the Golden State in 2012 and 2016, and the success of similar “tax the rich” measures on November 3 next door in Arizona (Proposition 208, on school funding) and Oregon (universal preschool). What went wrong?

PANDEMIC DISADVANTAGE

The most obvious element is the pandemic, which impacted the “Yes” forces far more than the other side. With a large labor/community coalition assembled early this year, the “Yes” campaign turned in the most signatures ever in California—1.7 million—to place the “Schools and Communities First” measure on the ballot, despite an early end to signature collection in mid-March due to the COVID-19 virus.

With the imposition of restrictions on public gathering and face-to-face contact, one of the main tools of labor-community coalitions against big money—grassroots people power—was diminished. No union or community group was willing to put its members in danger canvassing door to door. Large rallies were out, as was tabling in public spaces. The campaign did develop a robust speakers bureau program, including relational organizing efforts and battalions of letter to the editor writers.

Although Prop 15 phone banking was well-staffed with volunteers, voters couldn’t easily distinguish a volunteer from paid callers funded by predatory real estate corporations and large commercial property owners like Chevron. And weeks before election day, voter fatigue at the flood of calls rendered phone banks less effective.

SPLITTING THE BLACK COMMUNITY

Another problem was the role of the California NAACP. Usually a reliable partner in progressive ballot coalitions, the organization sided with the “No” forces. It is led by Alice Huffman, a former union staffer and state Democratic Party leader who has parlayed these credentials into a lucrative political consulting career. Over the years, this has devolved into a pay-to-play operation. Campaign finance filings show her firm accepted $740,000 in No on 15 contributions. The Huffman-led NAACP’s endorsement was useful in the massive direct mail operation that sent deceptive No on 15 literature streaming into African American households.

Huffman’s dual roles, while legal, drew sharp criticism. “I feel like it’s a conflict of interest and I think it’s misleading to the public,” said newly elected Oakland City Council member and local NAACP chapter officer Carroll Fife. Longtime organizer Anthony Thigpenn, president of California Calls, a key community organization in the progressive tax coalition, called Huffman’s actions “disappointing and sad.”

The NAACP position was countered by Prop 15 endorsements from other institutional pillars of the Black community, but it sowed confusion among African American voters.

The NAACP message echoed the general themes of the opposition campaign, which relied on fear-mongering and lies powered by an $80 million war chest. Although a court order forced the No campaign to rewrite its ballot guide arguments, calling them “misleading if not outright false,” the mendacious talking points continued to flow: Prop 15 hurt homeowners (Prop 15 excluded residential property); it was a massive tax increase on everyone (92 percent of the revenue would have come from 10 percent of the largest commercial properties); and small businesses would be crushed (properties worth up to $3 million were exempted). The “No” campaign zeroed in on economic fears during a pandemic depression and constructed a persuasive, if imaginary, world of pain for ordinary Californians should Prop 15 pass.

OUR MESSAGING

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Meanwhile, the “Yes” campaign emphasized the needs of public schools and local services and that big corporations and wealthy property owners should pay their fair share of taxes.

These points resonated but were not always posed as sharply as they might have been and, within the pandemic, were not sufficiently tied to deepening divisions between the rich and everyone else. The California Labor Federation—in its mailers—and the state’s Democratic Socialists of America chapters—which logged 300,000 phone calls to voters—promoted a more out front “tax the rich” line than the rest of the coalition. DSA phone bankers reported this clear and simple approach was well received and fit with voters’ experience of rising economic inequality.

Governor Gavin Newsom endorsed the measure late and did no campaigning for it. In contrast, in 2012, then-Governor Jerry Brown was out every day for weeks calling for the passage of Proposition 30, a “tax the rich” measure that passed 55-45.

Governors are media magnets. The No side outspent the pro-15 forces by some $20 million, most of which went to TV advertising. Newsom’s absence meant the loss of media opportunities that would have counterbalanced the negative ads.

Finally, the panic many voters felt at Trump-led attacks on the U.S. Postal Service generated a huge volume of early mail voting, which translated to less time for study of California’s lengthy and complicated list of ballot measures. Phone bankers reported many conversations to the tune of “Oh, if I had known that’s what Prop 15 did, I would have voted for it.”

Any one of these problems might have been overcome, but the combination proved too much to surmount.

NOT GOING AWAY

The result of the Prop 15 campaign does not mean progressive tax efforts are dead. The coalition that built this year’s effort has been around for close to a decade. As Matthew Hardy, communications director for the California Federation of Teachers, told me, “Between the chronic underfunding of public education and services and the added costs of the pandemic, something like Prop 15 remains absolutely necessary. The need for revenue is not going away, and our coalition is not going away either.”

Already last summer, some progressive state legislators proposed tax bills to tap the bank accounts of the richest Californians, which have swelled during the pandemic depression. Yet a legislative solution will not come easy. Ostensible Democratic supermajorities in both houses of government are reduced by a number of pro-business Dems. But without new revenues, the damage to the public sector will be severe. If the progressive tax coalition can get over the loss of Prop 15 quickly, it will have that message to work with.

Fred Glass is the retired communications director of the California Federation of Teachers, and the author of From Mission to Microchip: A History of the California Labor Movement (UC Press, 2016).

![Eight people hold printed signs, many in the yellow/purple SEIU style: "AB 715 = genocide censorship." "Fight back my ass!" "Opposed AB 715: CFA, CFT, ACLU, CTA, CNA... [but not] SEIU." "SEIU CA: Selective + politically safe. Fight back!" "You can't be neutral on a moving train." "When we fight we win! When we're neutral we lose!" Big white signs with black & red letters: "AB 715 censors education on Palestine." "What's next? Censoring education on: Slavery, Queer/Ethnic Studies, Japanese Internment?"](https://www.labornotes.org/sites/default/files/styles/related_crop/public/main/blogposts/image%20%2818%29.png?itok=rd_RfGjf)