Interview: If Only Unions Had Managed to Organize the South, Could Trump Have Been Avoided?

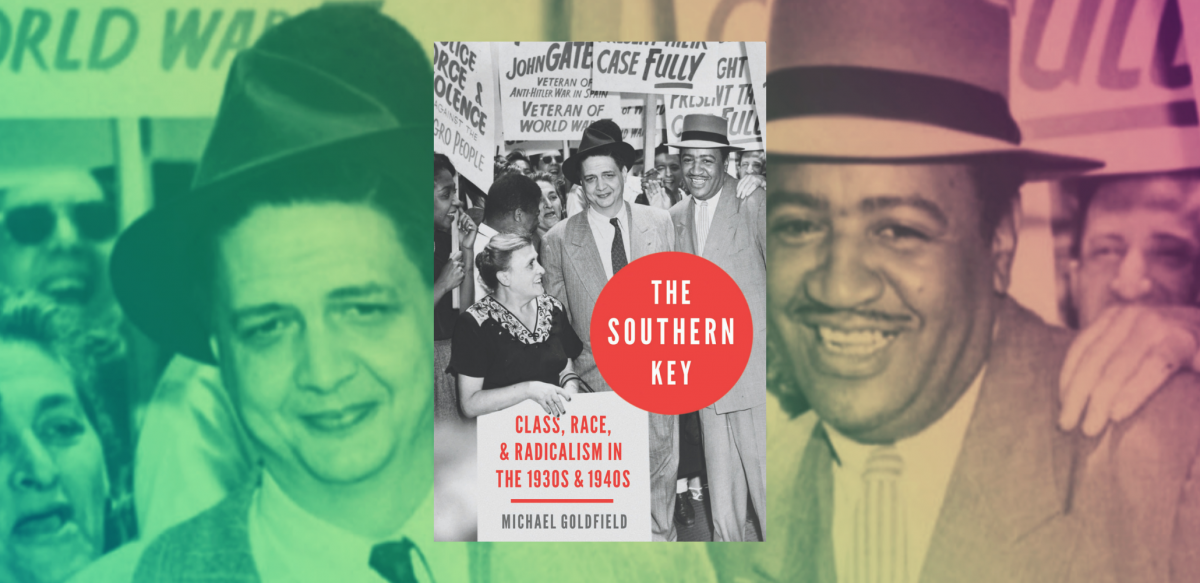

Michael Goldfield’s new book The Southern Key: Class, Race, and Radicalism in the 1930s and 1940s (Oxford University Press, 2020) provides some perspective on the enduring conservativism of the U.S.

At a time when activists and commentators are puzzling over the United States’ enduring conservatism, Michael Goldfield’s new book The Southern Key: Class, Race, and Radicalism in the 1930s and 1940s (Oxford University Press, 2020) provides some perspective.

Goldfield argues that the old question “Why no socialism in the U.S.?” reduces to “Why no liberalism in the South?” which itself is answered, in large part, by unions’ failure to organize the region in the early and middle 20th century.

The book consists of case studies defending this thesis and exploring what went wrong and how things might have turned out differently. Chris Wright interviewed Goldfield in early November about his arguments and his thoughts on the labor movement today. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Labor Notes: One of the major theses of your book is that the failure of the Congress of Industrial Organizations in the 1930s and 1940s to organize certain key industries in the South, such as woodworkers and textile workers, has shaped U.S. politics and society up to the present.

For example, the “liberal”—as opposed to labor—character of the civil rights movement, Republicans’ racist “Southern Strategy,” businesses’ relocation to the South in the postwar and neoliberal periods, and the conservative ascendancy of the last 50 years were all made possible by the CIO’s missteps. How did these failures to organize a few industries have such far-reaching effects?

Michael Goldfield: Underlying my argument is the unique ability of organized workers to engage in what I call civil rights unionism.

First, that includes demands inside the workplace for more hiring and upgrading of non-whites, especially women, desegregation of facilities, etc. Secondly, it involves broader struggles for desegregation, access, and other issues in the community at large.

Of special importance is the ability of organized workers to successfully resist right-wing, racist repression, something that was so successful in silencing individual white liberals in the South.

I discuss a number of such examples in the book, including the Farm Equipment Workers at International Harvester in Louisville and Local 10 of the Longshore Workers (ILWU) in San Francisco. These instances, though they provided clear templates for future struggles, were too isolated to affect the general course of events.

There is a clear contrast here with the Auto Workers (UAW) and the NAACP, the liberal civil rights organization. By 1945-46, the Auto Workers with Walter Reuther at the head had become very bureaucratic. They were on record as supporting civil rights, and Reuther was allied with the NAACP. But what did they actually do?

In Detroit, for instance, there were restaurants and bars around auto plants that were segregated, not allowing Blacks in. Reuther and the NAACP sent letters to all the bars and restaurants saying that they should integrate—and of course nobody did anything.

At left-wing locals, on the other hand, workers organized. Interracial picket lines went up around the restaurants and bars; the workers told the owners that if they didn’t allow Blacks in, they would have no business from anybody in the union. Instantly, owners changed their policy—thus demonstrating the effectiveness of civil rights unionism.

PICKET LINE FOR FAIR HOUSING

I can give you an example from my own experience, when I worked at an International Harvester plant outside Chicago. We had a Black worker in our plant who bought a house in a racist all-white community; his house was firebombed twice. Our group controlled the Fair Practices Committee, and we got the union local to vote to support a round-the-clock picket line at the house. Immediately, all the violence stopped.

Our plant was about a third African-American, and there were probably quite a few workers who were not sympathetic to what we were doing. But if any of us had been attacked, the whole local would have gone berserk. That type of strength that unions had when they were fighting for civil rights was different from most of what existed across the South.

The organizing of over 300,000 woodworkers (an industry that existed across the deep South, 50 percent of whose workers were African American) had the potential to make a tremendous difference. And if the Steelworkers (USW) and other unions had maintained their civil rights focus, the course of the civil rights struggle and of history might have been altered.

You’re very critical of the leaderships of both the CIO and the Communist Party in the 1930s–40s. Why did organizations that, for a time, showed such militancy and effectiveness in organizing particular industries (such as steel, automobiles, and meatpacking) fail so dismally to organize large swaths of the South?

I agree with Nick Fischer’s argument in the book Spider Web that liberal anti-communism, as practiced by the UAW under Reuther and the USW under Philip Murray, aligned itself with racists and fascists.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

In order to defeat the Communist leadership of the Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers, Murray and the USW allied themselves de facto with the KKK in Birmingham, destroying a progressive civil rights unionism (or at least weakening and limiting its influence) in Alabama. The CIO did the same in destroying the Winston-Salem Food, Tobacco, Agricultural and Allied Workers local.

The United Packinghouse Workers did not do this and continued to be a civil rights union. Auto, steel, and meatpacking actually were organized in the South. As Matt Nichter’s forthcoming article in Labor (“Did Emmett Till Die in Vain? Organized Labor Says No!”) shows, the UAW and USW had no rank-and-file civil rights presence, while the UPWA sent an interracial male and female Southern delegation to the Emmett Till trial in Mississippi.

GOLDEN OPPORTUNITIES SQUANDERED

Broadly speaking, the failure of interracial unionism in the South is attributable to three causes. First, the right-wing leadership of the CIO—the forefathers of the leadership of the contemporary labor movement—refused to seriously confront white supremacy in the South, squandering golden opportunities to organize Black workers in a number of large southern industries.

Second, the left wing of the labor movement—which had been the major goad behind interracial class unity in the first place—liquidated itself at the behest of the Soviet Union, which demanded labor peace during WWII, then limited its civil rights activity during the Cold War.

Third, the postwar red scare—including the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act—dealt a crippling blow.

You argue that in order for workforces to successfully organize, they generally need either “structural power” or “associative power.” For instance, coal miners during the period you write about had immense structural power and therefore tended to serve as a “vanguard” of the labor movement.

Textile workers, by contrast, lacked structural power, so they had to rely—or should have relied more than they did—on associative power, making alliances with other organizations and social forces.

Today, do you see any industries that have notable structural power and should be a prime target for organizers? Or do you think most workers now are compelled to rely primarily on associative power, on making connections with other groups and social movements?

Miners had structural power in part because they were providing the main fuel to the economy, which they don’t anymore. There are hardly any coal miners left in the United States, despite all the rhetoric.

But other people have the power to bring the economy to a halt, like truck drivers and others in the transportation industry. Airline workers could, potentially. They could have done it during the air traffic controllers strike, but of course the unions wouldn’t have considered that.

It’s interesting that workers in the food production industry and the warehouse and logistics industries are suddenly realizing how important they are, given the pandemic, and are mobilizing around their terrible treatment. There have been 44,000 cases of COVID-19 in the 100-plus meat processing plants and over 200 deaths. People are not happy about this.

THE PUBLIC SECTOR

In Detroit, where I am, bus drivers have struck over the lack of safety. It seems to be a generalized phenomenon that’s taking place, but I don’t know how to gauge it. I read Labor Notes and I subscribe to it, but its reporters are always seeing a new upsurge taking place. The United States is a big country and there are always strikes happening somewhere, but it doesn’t necessarily mean that a large movement is in the offing.

Still, we’re seeing people in places that were historically difficult to organize getting more upset and taking action. Many of the logistics hubs, for instance, are in the South. One of the biggest in the country is in Memphis, there’s a big one in Louisville, etc. These are urban, interracial workforces.

The South, of course, is very different now than it was in the 1930s and 1940s: it has much more economic dynamism, including a significant percentage of the auto industry, particularly transplants (foreign plants that have their production facility in the U.S.). While Detroit still has more auto production and more parts, there are huge parts corridors in states across the South.

Public service workers, too, are getting screwed really badly. The reason we had so many teachers’ strikes in so-called red states is that the budget cuts were much more severe there.

When these people struck, they had broad associative power and huge amounts of public sympathy. The Chicago Teachers Union organized parents and others in the community to support them, which hadn’t previously been done as much by teachers’ unions.

In West Virginia, a state that overwhelmingly voted both in 2016 and 2020 for Trump, schoolteachers were militant and had broad support throughout the state. The same was true in Oklahoma, and some of these same things happened in Mississippi.

So I think that the possibilities for a Southern upsurge, as well as in the country as a whole, are real. On the other hand, there isn’t the same insurgent, radical leadership that there was in the 1930s.

Do you see cause for hope that the kinds of errors the CIO made in its Southern campaigns—and that the AFL-CIO continued to make for decades thereafter—are finally being overcome? Do you think organized labor is starting to turn the corner?

No. While there are insurgent parts of the organized labor movement, including those who had threatened a general strike if Trump tried to steal the election, the AFL-CIO and its major unions, short of insurgencies and new leadership, are too rigid to lead the next wave of struggle.

Chris Wright has a Ph.D. in U.S. history from the University of Illinois at Chicago, and is the author of Worker Cooperatives and Revolution: History and Possibilities in the United States. His website is www.wrightswriting.com.