The Australian Green Bans: When Construction Workers Went on Strike for the Environment

The “Green Bans” were the first environmental strikes by workers. Almost a half-century later, they remain the largest and best example.

Imagine a building trades union that broke new ground in the 1970s in its support for environmentalism, community preservation, and women, and in its opposition to racism, even as it fought hard for all its members. Imagine a union that determined what got built, based on community interests rather than profit and greed.

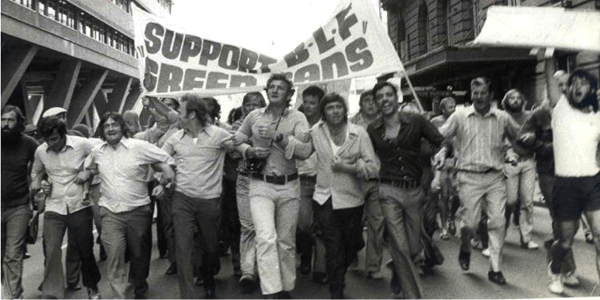

From 1971 to 1974, the New South Wales Builders Labourers’ Federation (NSWBLF) conducted 53 strikes. The strikers’ demands were to preserve parkland and green space, to protect the country’s architectural heritage, and to protect working-class and other neighborhoods from destruction.

The “Green Bans” were the first environmental strikes by workers; almost a half-century later, they remain the largest and best example.

Union leader Jack Mundey, who died on May 10, was mourned in Australia by labor militants, environmentalists, and preservationists. The movement he led is credited with saving Sydney—the country’s biggest city, where 42 of these strikes took place—by preserving its housing for working-class and other residents, its character, its open space, and its livability.

No corporate U.S. medium mentioned Jack’s death (or his life); both Mundey and the Green Bans are almost unknown here. But the Green Bans deserve to be well known, because alliances among labor, indigenous communities, communities of color, and environmentalists (such as under the umbrella of the Green New Deal) are crucial to our future.

BUILD IT NOW?

The NSWBLF’s approach was profoundly different from the approach of building trades unions in the U.S. at that time (and now).

In 1975, as I was installing ductwork in San Francisco on my first high-rise job, many co-workers walked out. Their demand was to move forward the Yerba Buena project in the SoMa District.

The delay was because of community demands, including the relocation of the working-class residents who were living in the single-room occupancy hotels that would be demolished. The building trades unions (along with big business and the city’s political class) were saying “Build it now,” even though retired union members were among those who would be thrown under the bus.

Moreover, the project would eliminate shops full of unionized blue-collar jobs, to be replaced by office buildings full of non-union jobs. I didn’t join the walkout.

DETERMINING WHAT TO BUILD

If the U.S. unions’ demand was “Build it now,” here’s how Mundey as secretary of the NSWBLF in 1972 saw it:

“Yes, we want to build. However, we prefer to build urgently-required hospitals, schools, other public utilities, high-quality flats, units and houses, provided they are designed with adequate concern for the environment, than to build ugly unimaginative architecturally-bankrupt blocks of concrete and glass offices...

“Though we want all our members employed, we will not just become robots directed by developer-builders who value the dollar at the expense of the environment. More and more, we are going to determine which buildings we will build...

“The environmental interests of three million people are at stake and cannot be left to developers and building employers whose main concern is making profit. Progressive unions, like ours, therefore have a very useful social role to play in the citizens' interest, and we intend to play it.”

TRANSFORMING THE UNION AND THE INDUSTRY

How did this view come to lead the union? In 1961, rank-and-file militants threw out a corrupt leadership that was complicit with the developers. Jack Mundey, Bob Pringle, Joe Owens, along with a number of other radical young union leaders, set out to rebuild the union in a way that was unusually democratic, breaking down the usual separation between leaders and members.

Union leaders were paid no more than workers. Union officials held office no more than six years before returning to “the tools.”

The leaders were all from working-class backgrounds. Almost all of them, including Jack, had not attended high school. They were definitely left-wing, but they avoided all left-wing jargon.

Union meetings were interpreted into up to seven languages, so the many immigrant workers could fully participate. Issues were decided democratically at membership meetings, rather than in back rooms. A woman member recalled “being able to participate in a near-perfect democracy.”

By the late ’60s, the union embarked on a comprehensive effort to transform the industry and the laborers’ terrible work situation. Wages were low and sometimes stolen due to crooked or undercapitalized subcontractors; working conditions and safety were horrendous.

In 1970, the union struck and won. Through their militancy and unity, the strikers won a reduced wage gap, so that laborers’ wages reached 90 percent of the craft workers’ wages.

The victory also reflected some recognition of the laborers’ increasing skill levels. Along with demolition, excavation, and pick-and-shovel work, because of the skyscraper boom they were doing much more rigging and concrete pouring and finishing, which no one would consider unskilled work.

While the union opposed the lack of planning and ugliness of the building glut, it also took advantage of the building boom to strengthen its hand. From 1970 to 1973, the workers won every major industrial action against employers, winning substantial wage increases and much greater safety. They went from sometimes not even having pit toilets to winning “amenities” such as hot showers, stoves, and fridges—none of which I ever saw on a U.S. jobsite!

ENCROACHING ON THE BOSSES’ POWER

More and more, the workers encroached on employers’ prerogatives. In the early 1970’s, the union fought for union hire and permanency in employment. The workers won the right to have first aid and safety officers on jobsites, and to elect those officers.

Workers, with full support from their union leaders, conducted mass stop-work meetings; interrupted concrete pours; and occupied jobsites. By striking a jobsite, they were usually successful in reversing arbitrary layoffs caused by mistakes the employer made, such as when necessary materials had not arrived.

They sabotaged scab work, while never physically attacking anyone. In one case, workers fired the foremen, threw them off the job, and elected their own.

The union ignored the rigged government arbitration court, relying instead on workers’ collective power to stop production. All these practices were threats not only to the employers, but also to conventional hierarchical and bureaucratic union leaders.

From 1961 to 1973, the union increased both its absolute numbers of members, from 2,500 to 11,000, and the percentage of workers who were union. Whereas previously, most laborers who were able to move to other types of work did so, now many members chose to stay in the industry, given the improved wages and conditions, and the excitement of exercising collective power.

WORKER POWER MADE THE GREEN BANS POSSIBLE

The Green Bans extended this encroachment to control of what was built.

The first Green Ban set the tone, relying on the remarkable cohesion and the militant spirit in the NSW branch of the BLF. When the union “banned” a building project by striking it, the developer tried to build it with scab labor. The union workers struck all the developer’s projects in Sydney. The ban held.

The Green Bans could not have been successful, or even occurred, without the first two steps: the building of a militant, democratic union, and winning big improvements for the workers.

The NSWBLF chose to be neither the initiator nor the arbiter of Green Bans. To start one, the community needed to show mass support for stopping a project, and ask at a public meeting for the union to impose a ban.

The union wanted to create a way for communities to weigh in on proposals. Community protests, petitions, and attempts to speak to officials were being ignored. Even legislatures didn’t have the power to stop a demolition. The BLF showed what a strategically placed, militant, and honest union with a social conscience could do.

ANTI-RACISM AND WOMEN IN THE UNION

The union’s activism was not limited to maintaining open space and the quality of the urban environment. Its work in fighting racism and sexism both reflected and helped create the social justice spirit of the times; these efforts involved Green Bans and more.

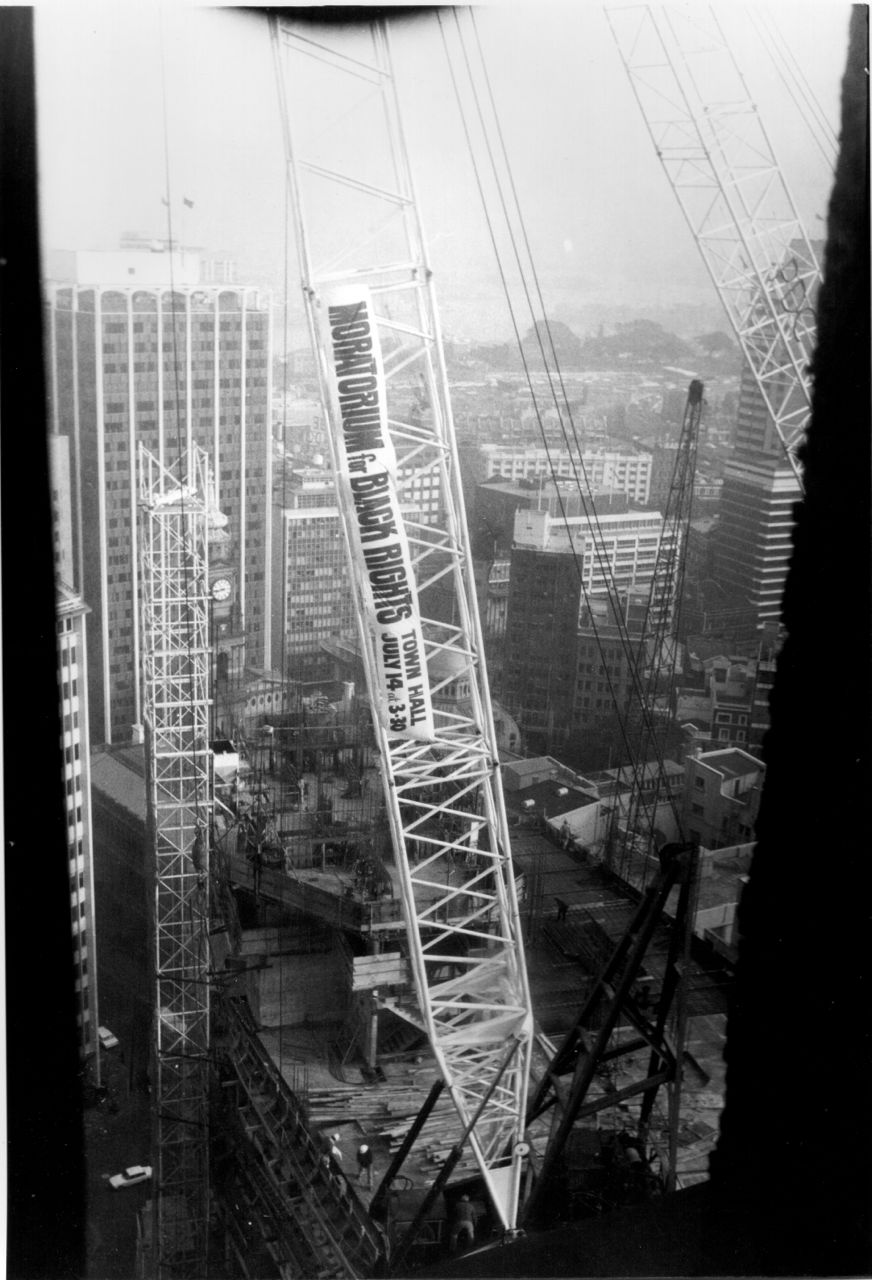

Racism in Australia, as in the U.S., stems from a history of British settler-colonialism. The union brought Aboriginal leaders to educate its members about their land struggles. The union politically and financially supported the growing Black (Aboriginal) movement, including the activists among its Aboriginal union members.

In late 1972, following the eviction of Aboriginal tenants, 18 Aborigines occupied two houses in Sydney that were slated to be demolished so that expensive townhouses could be built. The union banned the demolition and supported the occupiers’ demands; in early 1973, the new federal Labor government bought the houses and gave the area to the Black (Aboriginal) community. This became the country’s first Aboriginal land return—with 65 low-rent homes, a cooperatively run preschool, a cultural center, a medical center, and a food store.

The union supported the Black movement in many ways; when the union came under attack in 1974, 38 Aboriginal organizations pledged their support to the NSWBLF.

During the early 1960s, builders had hired women at lower wages, in jobs such as clean-up. The union won equal pay for women in the mid-’60s—whereupon the developers stopped hiring women.

Responding to the growing women’s movement, the union forced employers to hire women as full and equally paid members. By the end of 1971, there were nine women members. In 1972, several strikes occurred to force bosses to accept additional women workers.

The union banned a university building project until the university agreed to hire Women’s Studies instructors. It banned a building at another university that had expelled a student for being gay; the student was reinstated.

These are extraordinary actions for a largely male construction union. But they didn’t mean that sexism and homophobia no longer existed among the membership. The male workers fought the bosses for women’s rights in many instances, but elements of paternalism and subtle subordination remained.

Furthermore, even with strong support from union leaders, tradeswomen then (as here and now) needed well-developed interpersonal skills to negotiate working in a tough, male-dominated industry within a sexist society—skills not required of white tradesmen.

DEREGISTRATION

The NSWBLF leaders knew they would be attacked, big time. They had stopped construction worth $5 billion in 1970s dollars. Jack Mundey was once offered a $20 million bribe to approve a project, but the union leaders were incorruptible.

It took six months, but in March 1975 the NSWBLF was finally defeated, in an ugly and illegal process involving collusion among the corrupt head of the federal BLF, the Master Builders’ Association, and the corrupt, right-wing government of New South Wales.

The federal BLF burglarized the NSWBLF’s office and stole all its records. The federal BLF issued its own federal cards; the builders required workers to have these cards, and wouldn’t honor the NSWBLF cards.

When it came under attack, the NSWBLF got support from unions of teachers, telecommunication workers, and crane drivers (who had always participated in the Green Bans), along with civil society groups and the New Left.

But the Australian Council of Trade Unions (like our AFL-CIO) and the Building Workers Industrial Union (the craft workers’ unions) went against the NSWBLF. Few Labor Party politicians offered support.

Nineteen of the most prominent leaders were ejected from the union as it came under control of the federal union. Soon after this, women too were gone from the union.

In a final meeting with 2,000 members, the leaders encouraged the members to work with the Federal cards. Mundey, Pringle, and Owens were given a 10-minute standing ovation to honor their years of leadership.

LEGACY OF THE GREEN BANS

In spite of the union’s defeat, the Green Bans were successful because they did for the whole society what the union attempted to do in each Green Ban: they bought time, so communities could play big roles in deciding what got demolished and what got built.

By the time of the union’s defeat, the Green Bans had shifted the culture enough that the process for approving demolitions and buildings had changed. A Labor government came to power in New South Wales in 1976 and helped consolidate this process.

Social-movement unionism developed in many countries in the 1990s. Two decades earlier, the NSWBLF fully embodied and went beyond this approach.

The activist politician Petra Kelly was in Australia during the early ’70s, and started the Green Party in West Germany in 1979, inspired by having witnessed the Green Ban movement. This party and the other Green parties that subsequently formed in Northern Europe have been mostly progressive influences. Often they have joined Social Democratic or Labor parties to form a parliamentary majority. The Greens have typically joined the Labor parties in the degree to which they are pro-labor, and have also been able to push for environmental reforms.

After the union’s defeat, Mundey remained active in Australian and environmental politics. He spent time in Britain promoting worker/environmental alliances. He was invited to the U.S. to do a speaking tour in 1977, but his visa was denied due to the intervention of George Meany, then head of the AFL-CIO.

If Jack had made that tour, he and the Green Bans would be better known in this country—and alliances between labor and environmental movements might be farther along.

For further reading, check out Meredith and Verity Burgmann’s book Green Bans, Red Union: The Saving of a City (1998, 2017) or James Colman’s book The House that Jack Built (2016).

Steve Morse (steve_morse[at]mac[dot]com) is a retired member of Sheet Metal Workers Local 104.