Fed Up with Concessions, Detroit Teachers Kick Off School Year with a Strike

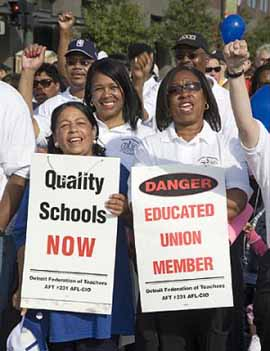

With a roar of applause and chants of "no contract, no work," thousands of Detroit teachers voted August 27 to walk picket lines rather than swallow $88 million in concessions.

"People were just fed up, plain and simple," said Karen Sepanski, an art teacher from Western High School. "They had a whole year to figure this contract out, and in the end the school board basically said 'take it or leave it.'"

The strike vote sent the 9,500 members of the Detroit Federation of Teachers (DFT) to the picket lines a week before the school year began.

Picketing was spirited, even defiant, in the opening days of the strike, providing some with a rare opportunity for teacher solidarity.

"We don't even have a teachers' lounge in my school," commented Sara Hennes, an English teacher from MacKenzie High School. "This was the first real group activity since I've been here. I got to know people better on the picket line than I did during the whole school year last year."

Although the walkout came as a surprise to many parents, as union leaders did relatively little to prepare the community for a possible strike, initial support was solidly behind the teachers. Polling showed nearly three-quarters of Detroiters sympathized with the strikers.

STRIKES BANNED

The union also initially received a sympathetic hearing from Wayne County Circuit Judge Susan Borman, who refused to grant the school district's first request for an injunction, instead ordering both sides into round-the-clock negotiations.

Public sector strikes are illegal in Michigan, and in 1994 the state legislature amended the law, requiring judges to order any striking public workers back to work. This move was a response to a bitter four-week strike by Detroit teachers in 1992. Judge Borman cited a 1995 court case that struck down key sections of the return-to-work legislation when refusing to issue an injunction.

Stymied in the courts, school administrators and some school board members played hardball with the strikers. Several principals responded to the walkout by threatening substitute teachers, who are part of the same bargaining unit as full-time teachers, with immediate dismissal.

School board president Reverend Jimmy Womack also stirred up tensions in the press, stating that union members didn't have to live with the strike's effects, a reference to the fact that more than half of Detroit's teachers live outside the city.

NECESSARY GIVEBACKS?

The strike represented an about-face for the DFT. Last year, confronted with similar demands from the school board, union leaders recommended a one-year contract with $63 million in concessions.

The school board pushed for even larger givebacks this time around, including a 5.5 percent pay cut for all teachers, a 25 percent cut in pay for long-term substitute teachers, and elimination of a planning period for elementary teachers. The board also pushed for teachers to shoulder an additional 10 percent of their health care costs.

With their pay already frozen, teachers were fuming over this year's proposed cuts. A move by the district to raise administrator salaries last spring only added fuel to the fire. "It's clear they are trying to balance the budget on our backs," noted Sepanski. "Don't take money out of my pocket, give it to administrators, and then turn around and come back for more."

DIFFERENT PRIORITIES

From the picket lines, teachers insisted that money was available to fund raises and preserve benefits. The problem, they argued, was the district's spending priorities.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Said Carmen Regalado, a DFT member and librarian at Martin Luther King, Jr. High School: "Teachers are asking themselves, 'Why is all this corruption [with school contracts] going on? Why are the administrators remodeling their offices with rosewood furniture? Why isn't the money getting into the classroom?'"

School board member Marie Thornton agreed that the district needs to take a closer look at how it spends its money: "I've pushed to overhaul all our contracts, both from the elected board and the appointed board...Some of them look like sweetheart deals."

Teachers were defiant as the judge's back-to-work order was read aloud at their September 10 mass membership meeting, vowing to continue the strike until a settlement was reached.

With little progress at the bargaining table, the union and the district were on a collision course for September 5, the first day of classes. Although the district tried to open on the first day, most of the 129,000 students stayed home. Superintendent William Coleman retreated the next day, canceling classes for the rest of the week.

On September 8, thousands of teachers surrounded the Fisher Building, where negotiations were being held. Later that day Judge Borman granted the school district's request for an injunction, ordering teachers back to work.

Teachers were defiant as the judge's order was read aloud at their September 10 mass membership meeting, vowing to continue the strike until a settlement was reached.

Entering its third week, the strike rapidly transformed into a political crisis, and state and local officials waded into the fray. After talks stalled September 11, Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick convened a late-night bargaining session in his office. Both sides emerged from the all-night talks bleary-eyed, but relieved-a tentative deal was in hand.

DFT leadership quickly ratified the agreement and brought it to a mass membership meeting on September 13.

The deal called for 3.5 percent in wage gains over the three-year contract and restored step increases frozen the year before. However, it also provided $39 million in concessions, forcing senior teachers to pay 10 percent of their health care costs alongside givebacks on bonuses and sick time.

BACK TO WORK

Members were divided over whether to call off the strike, but ultimately voted to return to work, effective September 14. "A lot of people left feeling very disappointed with the leadership," noted Hennes. "People were very confused going into that meeting, 'I don't know what to do, I don't know how to vote.' We wanted a good result, but this wasn't a good contract.

"My income will increase, but that doesn't make it a good result if most of the teachers end up losing money. Especially since we didn't get anything on the one thing most of us were really striking for-better conditions inside the schools."

"This is definitely not a victory," commented Regalado. "When we went back to work on Thursday, one of my co-workers said, 'I just took a $2,700 pay cut walking in the door.'"

Members will vote on the contract at their schools, with ballots counted October 6. Regardless of the outcome, the strike's aftermath is rippling through neighboring districts.

On September 13 teachers in Trenton, Michigan staged a sick-out over stalled contract talks, while negotiations heated up for more than a dozen other Michigan school districts that started the school year without a contract.