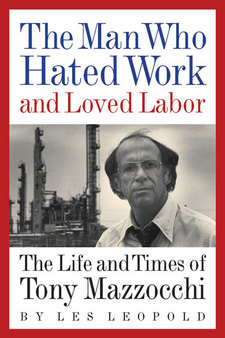

Book review: Tony Mazzocchi: The Man Who Never Sold Out

Tony Mazzocchi hated work. Don’t get me wrong. He was the hardest working labor leader I’ve ever met. The work he hated was the coerced, soul-numbing labor performed by untold millions in factories, offices and other hierarchical workplaces. Not only did most workers have their spirits crushed and their humanity demeaned on a daily basis, they were also routinely and knowingly exposed to toxic substances and hazardous conditions.

When I was a young union activist, it was Mazzocchi’s irreverent attitude to work that first endeared him to me. He was a breath of fresh air. “I’m not opposed to layoffs,” I remember him saying; “I just think that they should be done by reverse seniority. With full pay and benefits! It should be just like prison: you put your time in and get out.”

Les Leopold captures this sensibility and places it in a historical context in an important new biography on Mazzocchi’s life. An activist and leader in the Oil, Chemical, and Atomic Workers Union (OCAW, now part of the Steelworkers), his career spanned the entire second half of the 20th century.

A DIFFERENT KIND OF LEADER

Along the way Mazzocchi helped build one of the most dynamic and democratic local unions in the country, led the fight to liberate the OCAW from CIA-dominated business unionists, and birthed a powerful grassroots movement that established the legal right to a safe workplace. He linked that movement with the environmental movement, and was the key catalyst in the founding of the Labor Party, which he led until his death in 2002.

Tony Mazzocchi proposed an anti-corporate, alliance-building alternative to the mainstream post-war unionism that relied on cooperation between labor, management and government. “What Reuther was to building centralized bureaucratic unionism,” said long-time labor activist and sociologist Stanley Aronowitz, “Mazzocchi was to democratic unionism.”

In his two heartbreaking campaigns for OCAW president in 1979 and 1981 (he lost both races by less than 3 percent of the vote), Mazzocchi called for a mass labor mobilization to resist the growing global attacks on working people at a time when labor arguably still had the power to do something about it. When Ronald Reagan fired the striking air traffic controllers in 1981, Mazzocchi wanted to seize National Airport.

After being fired by the International, Mazzocchi helped mobilize the “lost battalions” of the labor movement to fight concessions and build solidarity throughout the 1980s. He later returned from political obscurity to win election as secretary-treasurer of the OCAW and used that position as a bully pulpit to pull together a national movement for independent labor politics.

SAFETY AND HEALTH PIONEER

Tony Mazzocchi is best known for his pioneering work around occupational safety and health, and Leopold’s book tells the stories of the uranium miners, asbestos millers, and chemical workers whose experiences gave rise to this movement. His chilling chapter on the Karen Silkwood case is the most succinct summary of her story yet written.

Mazzocchi drew on his experiences in the movement against nuclear testing to assemble a cadre of young scientists and doctors to provide validation and technical expertise for rank-and-file activists confronting the dangerous conditions under which they worked. Turning the top-down model on its head, these recruits empowered union activists and leaders to wage the fight on their own terms.

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

Mazzocchi also understood that the growing environmental movement was a natural ally. He pointed out that toxic exposures did not stop at the plant fence line and that the exposures suffered by workers were usually many times greater than those suffered in the community.

Mazzocchi insisted that unionists learn to take this alliance seriously and told environmentalists that their programs were doomed if they didn’t respond to the legitimate job concerns of those working in polluting industries. “There is a Superfund for dirt,” he would say, “There ought to be one for workers.”

The fight to establish the right to a safe job, according to Mazzocchi, would not be won by lobbying Congress, but would require a broad mobilization. In fact, he saw in this mobilization a powerful new lever that could revitalize a class-based movement of working people.

“A PARTY OF OUR OWN”

The nurturing and support of this movement was Mazzocchi’s life work and legacy. He thought a movement of this scope could only be built by “setting the terms of the debate”. Like all militant unionists, he understood that if you let the boss control what issues came to the bargaining table, you were bargaining against yourself.

Mazzocchi began calling for a labor party in the 1970s. In the late 1980s he was joined by the OCAW and many other unions and activists battered by the unrelenting corporate offensive. In 1996, the founding convention of the Labor Party attracted more than 1,500 delegates and the endorsement of six national and hundreds of local and regional unions.

Understanding how difficult it would be to build a labor party within the shell of the two-party system, Mazzocchi knew that a viable labor party had to be built upon the institutional support of organized labor. This would require finding ways to build the party’s strength while the unions continued to work for “lesser of two evil” Democrats. The party, he realized, must be provocative without being marginalized. And it would have to avoid both the narcissism of spoiler candidacies and the compromises of fusion parties.

Most of all, Mazzocchi understood that the fate of a labor party was entwined in the prospects for a dynamic, revitalized labor movement. Much as he predicted, the Labor Party grew during the brief labor upsurge of the mid-1990s and declined in the face of the defeats and demoralizations of the Bush years.

New York City labor leader Ed Ott recently called Mazzocchi “the man who never sold out.” Tony Mazzocchi’s life story has the capacity to inspire a new generation of activists. Mazzocchi would have looked at today’s crisis-ridden and divided labor movement as a passing phenomenon. He would have taken heart from the slow and steady progress of activists in South Carolina who are building a labor party in the heart of the right-to-work South and he would see the potential in the growing movement for national health care.

Mazzocchi would argue that, given the utter failure of the mainstream model, his alternative vision was bound to prevail. “They call me a dreamer,” he would say. “They call me impractical. But look at the mess that they’ve made of things. Isn’t it about time that we tried something different?”

Mark Dudzic is the national organizer of the Labor Party and former president of OCAW Local 149 and OCAW District 8 Council.