UConn Graduate Workers Press for a First Contract

Graduate employees packed a bargaining session to show their strength. Though their teaching and funding generates tens of millions of dollars for the university each year, they're paid meager stipends, and forced to return 10-22 percent of their incomes in student fees. Photo: GEU-UAW.

Joining the ranks of a resurging academic labor movement, 2,000 graduate workers are organizing for their first contract at the University of Connecticut.

Graduate Employee Union-United Auto Workers (GEU-UAW) Local 6950 won recognition last April with cards signed by 70 percent of the bargaining unit. It’s the first of its kind in Connecticut—and now the largest union at UConn, where faculty and most staff have been organized for years.

Each year, graduate workers at UConn help teach thousands of students and conduct research that generates tens of millions of dollars in funding. But in the wake of the recession, they’re bearing the brunt of declining state support for higher education.

EXORBITANT FEES

Mandatory graduate student fees at UConn have rocketed up over the last decade, far surpassing the national average at peer institutions. This year, they totaled a whopping $2,270. These fees are often used to finance projects unrelated to graduate work or the school’s academic mission—such as the planned construction of a $100 million recreation facility.

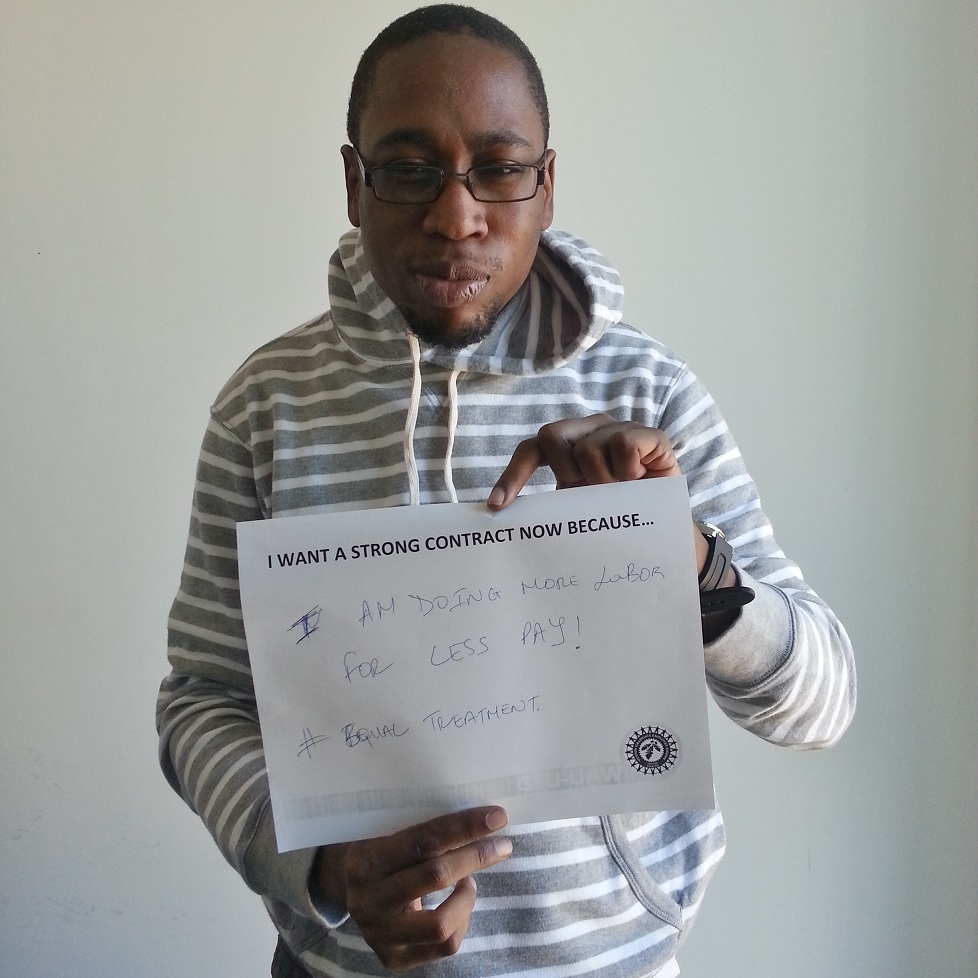

Through fees, graduate workers contribute 10 to 22 percent of their incomes back to the university.

Meanwhile, the stipends they’re paid have stagnated. Full-time graduate workers receive $21,000 to $24,500 during the academic year, depending on their professional levels. Some programs don’t even offer full-time assistantships, so graduate workers in those fields have to make do with much lower part-time stipends.

On top of that, major changes in the graduate workers’ health insurance plan in 2013 made coverage less affordable. For those with dependents, the change was drastic.

By fall 2013, after enduring a series of unilateral decisions, graduate workers were talking about unionizing.

The final straw for some, according to Maria Seger, a doctoral candidate in the English department, was when university administrators suggested a possible response to budget cuts: increasing certain teaching assistants’ workloads, without raising their stipends to match.

“We realized how vulnerable we were,” Seger said. “Our desire for change was greater than our fear of what would happen if we demanded it.”

ROBUST INTERNAL NETWORK

Before reaching out to the UAW, the graduate workers began to develop a robust internal network of their own. The tactical challenge of organizing a large, diverse workforce required rank-and-file activists to mobilize in the university’s numerous departments.

A growing group did electronic outreach, held information sessions, and made presentations to the Graduate Student Senate, which later passed a resolution backing unionization.

Through conversations, examining bulletin boards, and digging up listservs, they compiled a comprehensive list of graduate workers at the university.

An organizing committee soon convened regularly to spearhead the campaign. Each rank-and-file organizer was assigned to collect cards in a handful of departments and to recruit leaders in labs and offices.

Leland Aldridge, a doctoral candidate in the Physics department, said the energies of “a dedicated core [of activists] willing to make the union their priority” distinguished this fight from failed attempts to unionize at UConn in the past.

In a remarkable display of grassroots support, dozens of graduate workers—representing almost every department—agreed to have their names publicly listed on the union authorization cards, before these were distributed to all bargaining unit members.

The vast majority of cards were signed through one-on-one conversations between graduate workers. Seger said this organizing strategy helped build mutual respect and solidarity across the campus’s disparate academic disciplines.

GOT NEUTRALITY

SUPPORT LABOR NOTES

BECOME A MONTHLY DONOR

Give $10 a month or more and get our "Fight the Boss, Build the Union" T-shirt.

UAW Region 9A Director Julie Kushner said last year’s graduate worker victory at New York University, made possible in part by a neutrality agreement, added momentum to the UConn campaign and inspired the decision to fight for a similar arrangement.

Nationally, the UAW now represents more than 25,000 graduate workers. Most are at public institutions such as UConn, since the National Labor Relations Board still hasn’t ruled on whether it will force private institutions to bargain with graduate workers.

Private employers can still voluntarily recognize unions. At NYU, after an unsuccessful strike for recognition, graduate employees battled for eight years before administrators finally agreed to neutrality.

But at UConn, things moved at a much swifter pace. It might be the fastest organizing drive ever to succeed among graduate workers in the U.S.

To win neutrality, the graduate employees worked to develop their political leverage. Connecticut is one of seven states that preserved a Democratic trifecta—control of the governorship and both state legislative houses—in the recent midterm elections, owing to the power of the local labor movement.

So union activists traveled to the state capital to ask elected officials for their support—and they got it. Connecticut’s seven-member Congressional delegation sent a letter to the UConn administration advising neutrality. Other backers included the lieutenant governor, attorney general, secretary of state, treasurer, comptroller, and 70 state legislators.

The combination of rank-and-file activity with political pressure quickly produced a neutrality agreement. And the union took advantage of a rarely-used Connecticut law provision that permits card-check elections in the public sector.

GEU-UAW was certified by the State Labor Relations Board and recognized by the university in April 2014—an unusually rapid win.

STILL ON OFFENSE

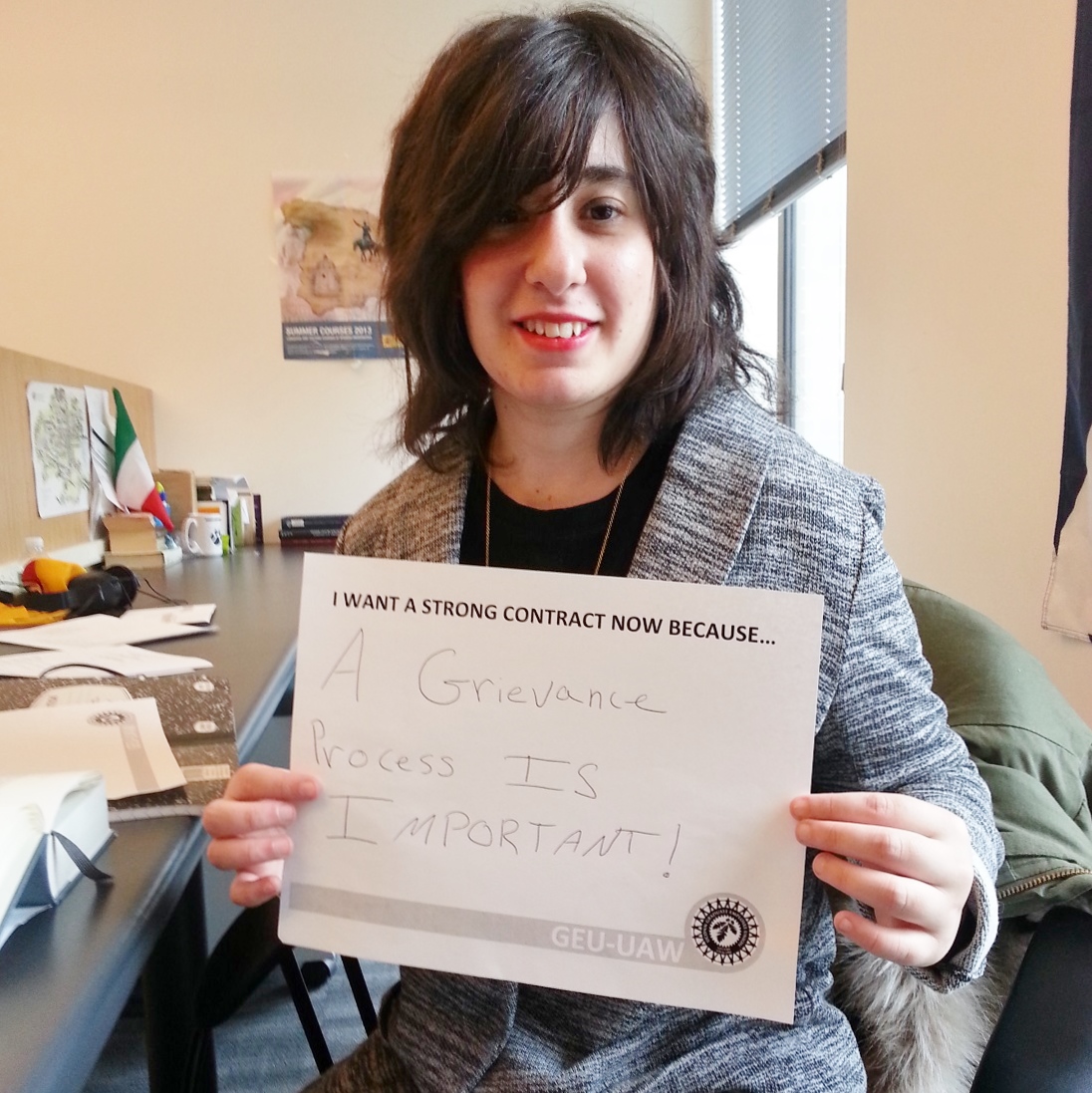

Since then, UConn graduate workers have been agitating for a first contract. They elected a bargaining committee, and a majority of workers filled out bargaining surveys.

“Because we can’t strike, we have to be more strategic about how we build power,” said Cera Fisher, a member of the elected bargaining committee.

Connecticut law forbids public sector workers to strike, but they do have the right to binding arbitration. So the graduate employees are hoping their continuing majority-support actions and the prospect of arbitration will compel the university to agree to a fair contract in a timely manner.

In August, a large delegation of graduate workers showed up at the second bargaining session to demonstrate their power, holding signs to identify the variety of their departments.

A month later, 100 graduate workers wearing “Working for a Better UConn” shirts visited the public comments segment at a board of trustees meeting to deliver a petition signed by a majority of the bargaining unit urging the university administration to expedite the negotiations schedule.

Recently a majority vote authorized the bargaining committee to invoke arbitration, in case it needs to. And a “work in” is planned February 18-19.

GEU-UAW’s bargaining team says it intends to build on the contract standards that UAW-represented graduate employees have won at the University of California, the University of Massachusetts, and the University of Washington, including workload protections and improved health care benefits.

Meanwhile in New York City, NYU graduate employees are fighting for a contract too. And graduate workers at two other private institutions, Columbia University and the New School, filed petitions in December to join UAW Region 9A.

Puya Gerami is an organizer for SEIU District 1199 New England. He can be reached at puya.gerami[at]gmail[dot]com.

CORRECTION: The recently filed representation petition at the New School includes not only its social science division, the New School for Social Research, but also all its other divisions, such as Parsons and Milano.